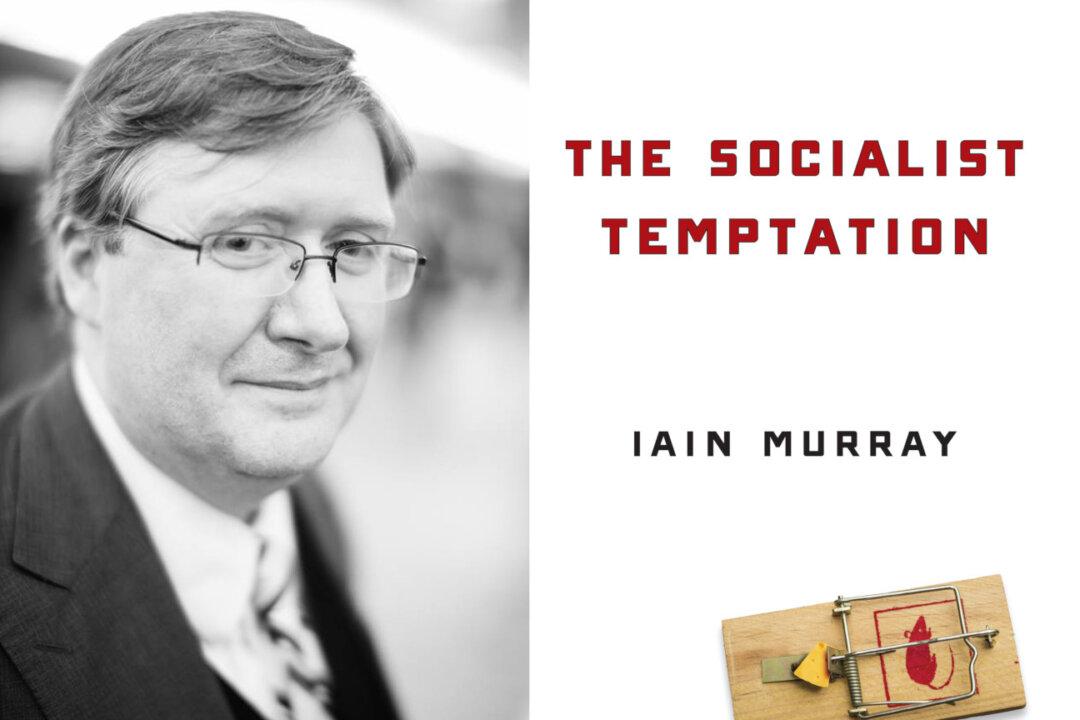

Support for socialism in America isn’t new, nor is the successful push for socialist policies. It seems to reemerge every few decades, but what’s new this time, according to Iain Murray, is a much poorer understanding of what socialism actually is.

“At the moment, it’s hard to pin down what they mean by socialism,” said Murray, who directs the Center for Economic Freedom at the Competitive Enterprise Institute in Washington.