Let us look deeper at what has occurred to the state of realism. The writer Jean-Jacques Rousseau said, “Men are born free, but everywhere they are in chains.” Let’s substitute “artists” for “men” and we have a declaration that more accurately describes that state of the art world through most of the last century. “Artists are born free, but everywhere they are in chains.”

Artists have been virtually (if not actually) imprisoned—whether we are talking about the chained constraints of “conceptual art” or the drudgery of “deconstruction,” the “shackles of shock” or being mired in “minimalism,” or the vapid, inane impoverishment or works described as “abstract.”

All are chains that have been “forged link by link and yard by yard,” paying lip service to composition and design, while long ago having abandoned all of the parameters of fine art.

If we look more closely, we can see that for most of the past century, there has been an ongoing attempt to malign and degrade the reputations and artwork produced during the Victorian era and its counterparts in Europe and America.

Sadly, they were very successful. But in the past 30 years, it has started to change.

I tend to think of 1980, when the Metropolitan Museum took some of its finest academic paintings that had been in storage since World War I and hung them in the new André Meyer Wing, and announced its decision to the world.

Hilton Kramer of The New York Times led a journalistic assault against the Met, and excoriated them for daring to hang William Bouguereau and Jean-Léon Gérôme next to Goya and Manet.

I was even more outraged at Kramer’s remarks than he was at what the museum had done, and after failing to get them to publish an op-ed response, I had to pay for the space in the Sunday New York Times Arts and Leisure section in order for people to hear a responsible rebuttal.

It ran twice, and I received dozens of supportive letters, including one from Thomas Wolfe whose sympathizing beliefs were expressed in his legendary book titled “The Painted Word.” Fortunately the Met stuck to its guns, and today that section has expanded considerably, though there are still masterpieces in its vaults that remain underappreciated.

Over the past three decades, I and other art historians have done a great deal of research and found an overwhelming preponderance of evidence that proves that the modernist descriptions of this era are no more than lies and distortions fabricated in order to denigrate all of the traditional realist art produced between 1850 and 1920.

Emile Zola’s novel “The Masterpiece” was a fictional story about impressionist painters being mistreated by the officials of the Paris Salon run by the academic masters of that time. This totally made-up account of what occurred amazingly started to be written into art history texts as if it all had actually occurred, and to this day, the heart of modernist accounts of the art history between 1850 and World War I is based on this book’s tale of woe.

The suppressed truth about this period, however, is that during the 19th century, there was an explosion of artistic activity unrivaled in all prior history.

Thousands of properly trained artists developed a myriad of new techniques and explored countless new subjects, styles, and perspectives that had never been done before. They covered nearly every aspect of human activity. They were the product of the expansion of freedom and democracy and a profound respect for human beings. They helped disseminate the growing view that every individual was valuable, that all people are born with equal inalienable rights—especially the rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

This is Part 6 of an 11-part series presenting the speech given by Frederick Ross at the February 7, 2014, Artists Keynote Address to the Connecticut Society of Portrait Artists. Frederick Ross is chairman and founder of the Art Renewal Center (www.artrenewal.org). Read previous parts here.

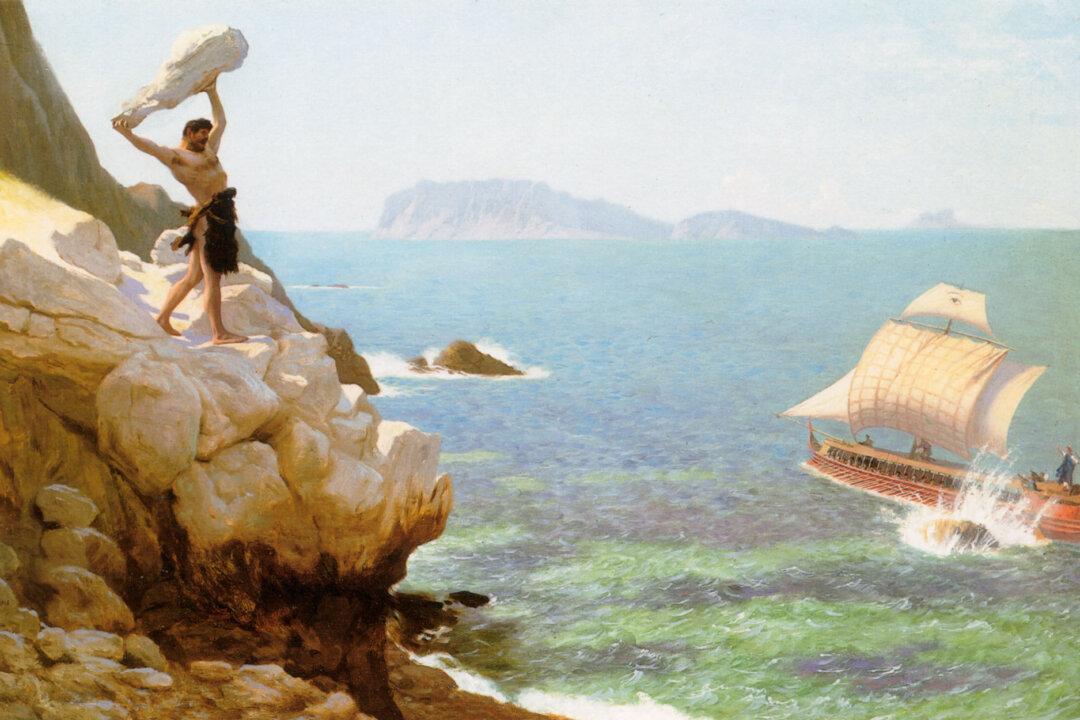

“Polyphemus” by Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904).

Courtesy of Art Renewal Center

|Updated: