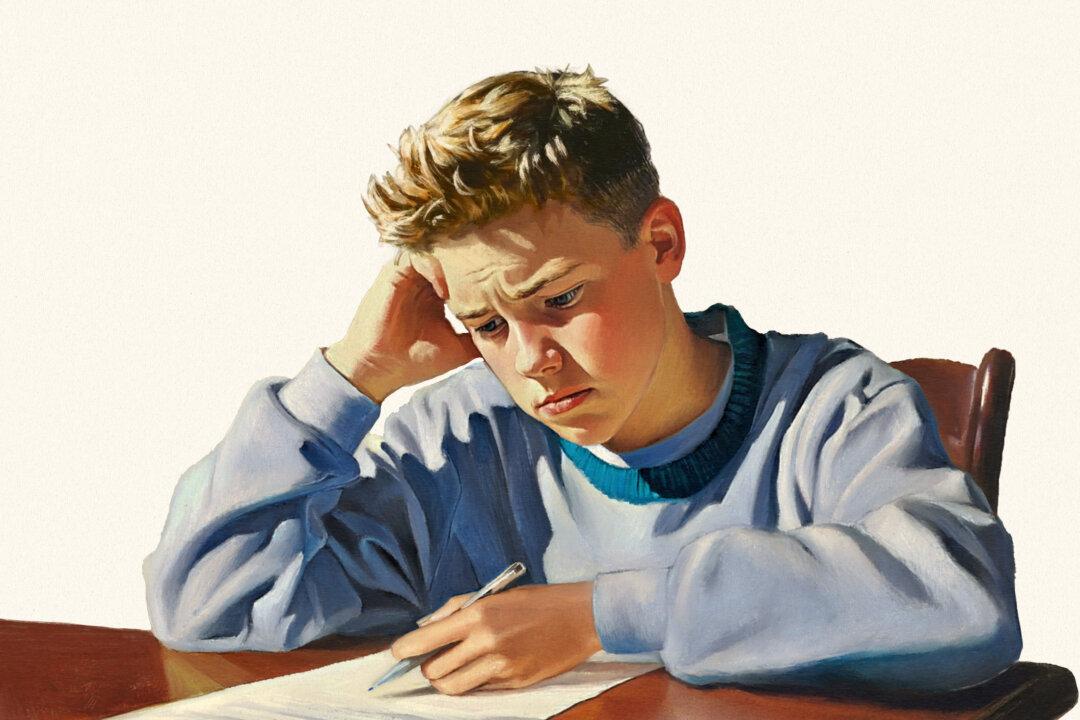

Only 20 percent of boys in the United States are proficient in writing by eighth grade, according to Warren Farrell and John Gray’s 2018 book “The Boy Crisis.” The authors reveal that the number of boys who dislike school has ballooned by 71 percent since 1980, and boys are much more likely to be expelled than girls are. Boys’ educational woes don’t end with high school; young men now account for only about 39 percent of college degree recipients, a precipitous decline since 1970, when they earned 61 percent of degrees.

Dr. Leonard Sax rang the alarm bells on this concerning trend back in 2007 in his book “Boys Adrift,” writing that “what’s troubling about so many of the boys I see in my practice … is that they don’t have much passion for any real-world activity … They disdain school because they disdain everything. Nothing really excites them.”