Learning a foreign language is always a good thing: It gives one a chance to compare and contrast the new language’s structure, the shape, the anomalies with one’s own. It can also bring to mind psychological and quirky ideas overlooked in one’s native language. Take for example, the words for “the poet” in Italian: “il poeta.” The anomaly is that most masculine nouns in Italian end in “o,” while most feminine nouns end in “a.” Yet the “il” signifies a masculine word, a masculine word with a feminine ending. There are other examples of this phenomenon, but I think this is a particularly interesting one.

Getting to the Root

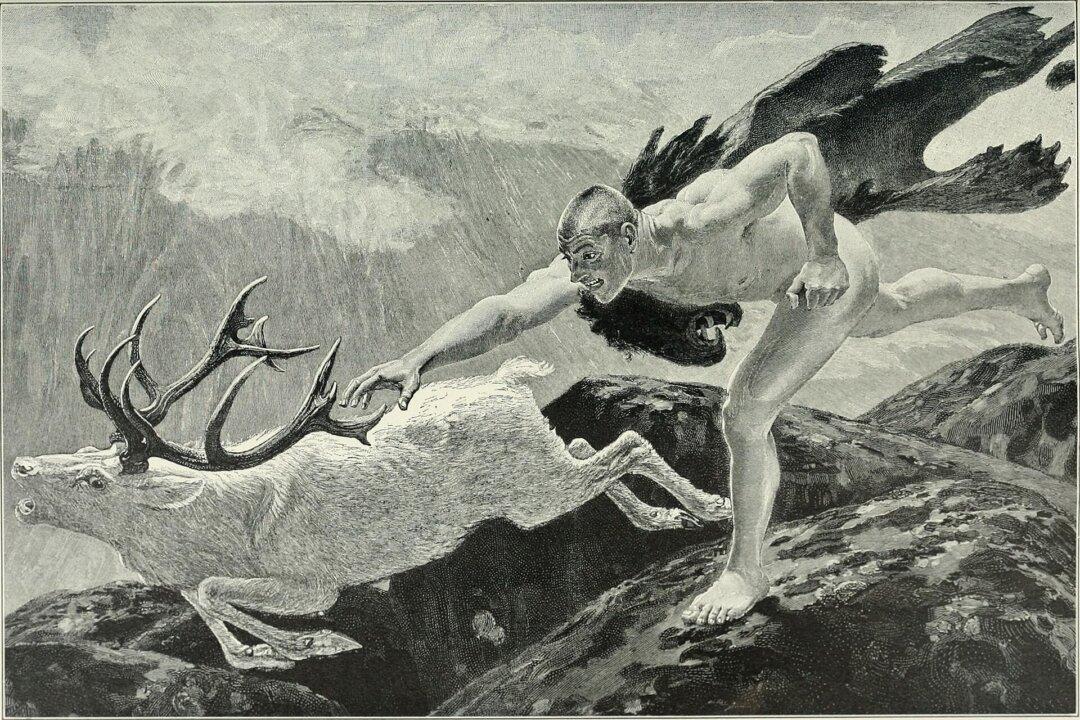

"Inspiration," 1769, by Jean-Honoré Fragonard. Oil on canvas. Louvre Museum, Paris. Public Domain