No matter how much you prepare and train however, things seldom go as expected. You can create a plan of action for just about any mission, and run countless training exercises prior to launching the operation, only to have things go off the rails within the first few minutes. That is simply the nature of things, and not all variables can be accounted for nor can they be predicted. SEALs believe that you should “plan your dive and dive your plan,” but it often does not work out that simply. That leads to another very important lesson that I learned from my time as a SEAL: always include contingency plans while training and remember to be flexible. You’ll want to be able to roll in another direction when things truly go bad.

The best laid plans can easily come undone and quite frankly we should always expect them to. Prior to any mission we would come up with numerous contingencies, trying to consider all of the potential “what if” scenarios we could face during a mission. But even with years of experience and training there was still no way to predict everything that could potentially come our way. That meant we had to be light on our feet, quick thinking, and highly adaptable.

We’d also tell ourselves, “If you’re going through hell, don’t slow down. Just stay focused on the mission.” The point was that things rarely went as we had hoped, but that shouldn’t matter. We had a job to do and everything else was secondary. If you can keep your eyes on the prize, you’ll have a much better chance at being successful.

This same attitude has served me well throughout my athletic career, too. When competing in an endurance event that goes on for hours or even days at a time, things are bound to go wrong at some point. Muscles, tendons, and ligaments are subject to damage, bikes have mechanical breakdowns, teammates collapse and take ill, and sometimes you find yourself way off course. Learning to take those things in stride is crucial to reaching your goals, because the path to success is almost never as straight and easy as we’d like to believe it will be.

I can’t even begin to count the number of times that things went poorly in the middle of a training exercise or mission. Being able to stay calm and recall my training saved my life and those of my teammates on many occasions. Of course, there were also more than a few painful lessons along the way.

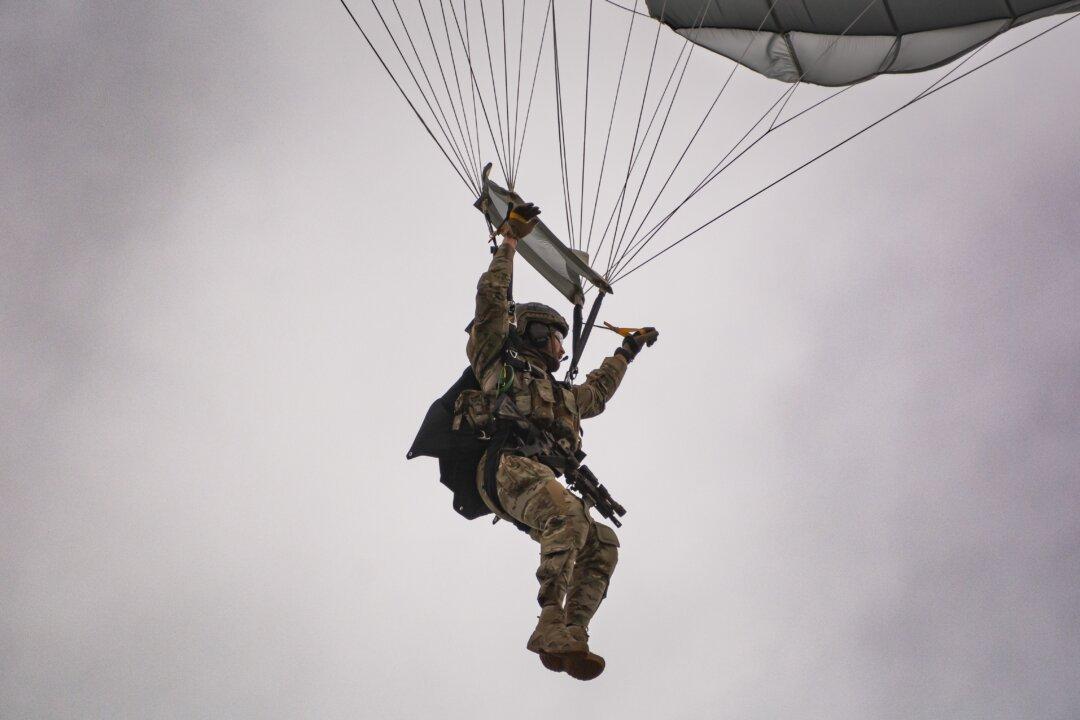

For instance, one time while training for a high-altitude, high- opening (HAHO) parachute insertion, I found myself in a particularly precarious situation. With a seventy-five-pound pack on my back, a helmet on my head, my weapon strapped to my side, and an oxygen tank and mask locked in plaice I jumped out of a perfectly good aircraft at just over 18,000 feet. I ended up having an absolutely terrible exit, flipping through the risers on my parachute as I hit the night air. The risers twisted and smashed down on my helmet causing my head to violently snap to the left, ripping the O2 mask off of my face and sending a sharp pain down my body. I saw a white flash and, in that moment, I was sure that I had broken my jaw and neck.

While there was obviously cause for concern, I had other problems to contend with as well. Thanks to my poor exit, I was falling through the pitch-black night like a rock. All I had overhead was a crumpled malfunctioning parachute that was doing nothing to slow my fall.

I had to react quickly or I would hit the ground at terminal velocity. We jokingly called this type of death, “deceleration sickness.” Fortunately, we had trained for these kinds of contingencies, so I knew just what to do.

Using my right hand, I pulled the cutaway pillow and released my main parachute, which instantly shot off overhead, disappearing into the night. Then, with my left hand, I pulled the reserve chute, which mercifully deployed as expected.

With things now a bit more under control, I was able to get my O2 mask back on and suck in some oxygen. I reached for my push- to-talk comms unit to let the other SEALs on the jump know what had happened. I could see their chemical light sticks high above me. We were traveling in the same direction, but I was now thousands of feet below the rest of the team.

I wanted to give them an update on my status and tell them that I would join them as quickly as I could once we were all on the ground. But as I tried to talk, all I could manage was an unintelligible mutter. I may have been able to right my fall and avoid crashing into the ground, but there was still some other issues I needed to resolve.

When the risers on my main chute snapped my head back, they had dislocated my jaw, making it impossible to talk. As a corpsman however, I had dealt with these issues on others plenty of times before and knew exactly what to do. Applying pressure on my back- bottom teeth with my thumbs and I was able to snap my jaw back into place with a single swift firm motion. There was loud pop followed by a searing pain, but everything was back to where it needed to be. After that, I was able to radio the rest of the team to let them know I was safe and I would rendezvous with them as quickly as I could.

On another occasions I ran into a problem that nearly cost me my life. We were practicing a static ship takedown, which is an operation that tasks SEALs with approaching a vessel from under the water. The SEALs silently board the target vessel by climbing to the deck of the ship using a caving ladder and a telescopic pole, and then undertake a hostage rescue and terrorist take down. These were the kinds of missions that we trained for and conducted all of the time and we were proud of our reputation for being the absolute best in the world at handling those kinds of situations.

On one such training exercise we were in the middle of a night dive using oxygen tanks when things started to go bad. It is important to note that when you’re breathing 100 percent pure oxygen you can only remain submerged for about four hours at a depth of thirty feet before the O2 starts to become toxic. When you hit that four-hour mark, divers can experience convulsions and seizures that can quickly lead to death.

Our dives were always at night and the dive team all dove together, a feat which is extremely hard to do. In low-light conditions and in often murky water it was difficult to see anything. Worse yet, it was practically impossible to communicate with the other SEALs using anything other than hand squeezes.

After we finally identified our target ship, we prepared to derig our gear and board the vessel. Once in position, we removed our fins, weight belts, and Dräger rebreathing units, connecting them on to the line that we had rigged under the ship. The O2 Dräger was the preferred rebreather units for Navy SEALs because it didn’t give away our position underwater. Unlike when using SCUBA gear, there are no air bubbles that rise to the surface while exhaling.

After waiting ten or fifteen minutes while breathing from my Dräger attached to my derigging line, I suddenly realized that I couldn’t breathe at all. Something was wrong, and I wasn’t sure what the problem was. I told myself to remain calm and methodically I began checking my equipment. We had SOPs (standard operating procedures) for most everything we did. First, I ran my hand up the inhalation hose to be sure it hadn’t gotten kinked or twisted somehow. When I couldn’t find any problems there, I moved on to the oxygen tank itself, thinking that perhaps the valve had somehow gotten turned off. It hadn’t; it was wide open. I also double-checked that the mouth piece valve had not been inadvertently turned to the off position. These were all of the SOPs I was trained to conduct, but I still couldn’t breath!

Calmly and carefully I repeated the same procedure three times, all the while my lungs were starting to burn and my head was really hurting. I was quickly running out of time, but I wasn’t any closer to getting to the bottom of the problem.

Finally I reached up to my buddy’s fin and shook it. He came back down to meet me. We couldn’t see each other since it was pitch dark, but when I could feel his presence, I reached out toward his face with my hand to see if I could feel for his mouthpiece. He had already derigged and did not have his Dräger on, so I was unable to buddy-breathe.

Starting to get a bit more concerned, I repeated my emergency SOPs one more time: I needed to act fast or I was going to be in real trouble. My head was pounding and my body was aching to take a breath. We had one rule of engagement and that was not to get caught on this hostage rescue mission. I was about ready to blow the entire mission because I needed to take a breath, but I wasn’t about to let that happen.

To complicate things even further, the ships that we trained on were huge. As a diver, you really don’t have a good idea where you are under these massive floating structures. I started to swim up to the surface, heading towards the hull of the ship where I hoped I could find a spot to catch a breath without compromising the mission. In the darkness it was impossible to see where the vessel was above me, so I just put my hand over my head as I kicked upward to avoid slamming into it.

The ship was adjacent to a large buoyant structure and there was absolutely no room for me to squeeze between the two objects. By now, my brain felt like it was being stabbed with an ice pick as my oxygen levels began to deplete. I had no other option but to ignore the pain and press on. As I was taught in BUD/s just keep kicking and don’t quit. So I kicked.

It had been quite a few minutes now without breathing. My head felt like it was going to explode. It was getting colder as I kicked and I realized I must be going deeper. I had two thoughts, aside from to keep kicking. One thought was to just take a deep breath and the pain would end. I would simply drown but I wouldn’t blow the mission. My second thought was, how would they ever find my body under this huge ship. Later, I was disappointed in myself for having those thoughts because I know that was exactly how a quitter would think.

So I kicked and kicked and eventually spotted a faint light in the distance. I swam under the boat from approximately midship to bow. As I surfaced, I pulled my mask down below my chin in order to avoid giving away my position with light reflecting off the glass. I was still following standard operating procedure even then so I would avoid blowing the training exercise.

After regaining my composure and saying a few prayers, I swam down the port side of the boat and joined my teammates, who were just climbing the ladder and preparing to board the ship. As I looked back across the water, I realized that the light that I had seen was cast by the moon, and it was just pure luck that I caught a glimpse of it at all.

Later in a post mission debrief, I would learn that my rebreather had a rare malfunction that caused its inhalation hose valve to freeze shut, closing off my air supply in the process. I was extremely lucky to come out of that situation alive. Without my training, which taught me to remain calm and composed under pressure, I wouldn’t have survived.

The ability to stay flexible and think on your feet is a trait that everyone should master. Whether you’re caught up in a heat-of-the- moment situation like the ones I’ve described, or you experience something less urgent but equally important, being able to switch gears, come up with an alternate plan of action, and initiate that plan is crucial. Everyone encounters those moments at some point in their life, but those with a strong mindset who are focused on reaching their goals will learn not to freeze under pressure. Instead they’ll see alternate ways of reaching their objectives even as chaos surrounds them.

(To be continued...) This excerpt is taken from “Reaching Beyond Boundaries: A Navy SEAL’s Guide to Achieving Everything You’ve Ever Imagined” by Don Mann and Kraig Becker.

To read other articles of this book, click here.

To buy this book, click here.

This excerpt is taken from “Reaching Beyond Boundaries: A Navy SEAL’s Guide to Achieving Everything You’ve Ever Imagined” by Don Mann and Kraig Becker.

To read other articles of this book, click here.

To buy this book, click here.

The Epoch Times copyright © 2023. The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors. They are meant for general informational purposes only and should not be construed or interpreted as a recommendation or solicitation. The Epoch Times does not provide investment, tax, legal, financial planning, estate planning, or any other personal finance advice. The Epoch Times holds no liability for the accuracy or timeliness of the information provided.