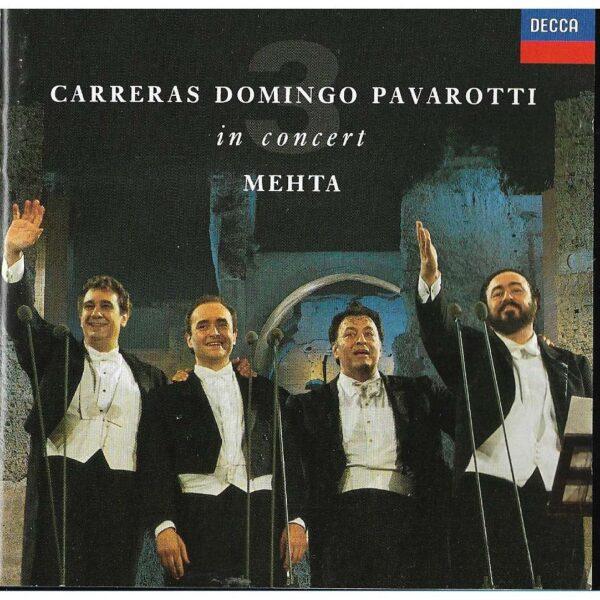

It seems we classical musicians feel lucky if nowadays the general public has any familiarity at all with classical music. We don’t even mind if a certain amount of music gets called classical that didn’t used to be. It was way back in 1990 that the Three Tenors won a Grammy for “Best Classical Vocal Performance” with a CD that included “Memory” from the musical “Cats,” the 1940s French pop hit “La vie en rose,” and the “West Side Story” songs “Maria” and “Tonight.”

The Grammy-winning album “Carreras Domingo Pavarotti in Concert” (1990) with (L–R) Plácido Domingo, José Carreras, conductor Zubin Mehta, and Luciano Pavarotti. Decca