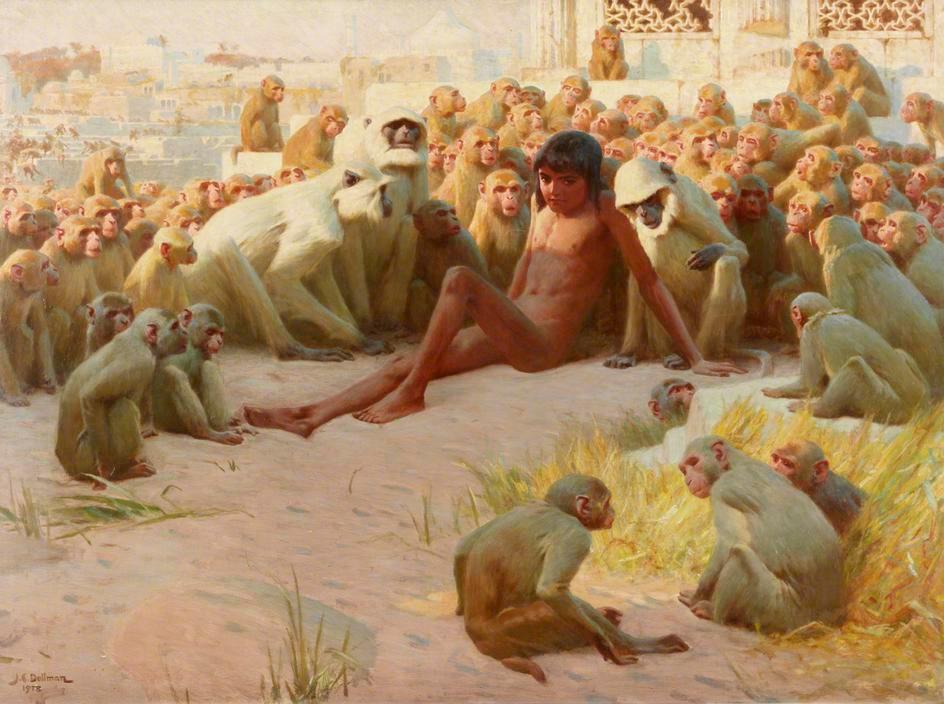

My heart leaps up when I behold A rainbow in the sky: So was it when my life began; So is it now I am a man; So be it when I shall grow old, Or let me die! The Child is father of the Man; And I could wish my days to be Bound each to each by natural piety.

The Fox whispered to the Little Prince in Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s time-honored tale, “It is with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.” And the language of the heart that speaks what it sees is poetry.William Wordsworth speaks this language fluently in his evocative little paean to a life of wonder in “The Rainbow.” Written on March 26, 1802, in the Lake District of northern England, the famous Romantic poet gives voice to those urges of pure emotion and heartfelt desires that beauty evokes, which is the child’s being and the man’s blessing.