By Lila Seidman

From Los Angeles Times

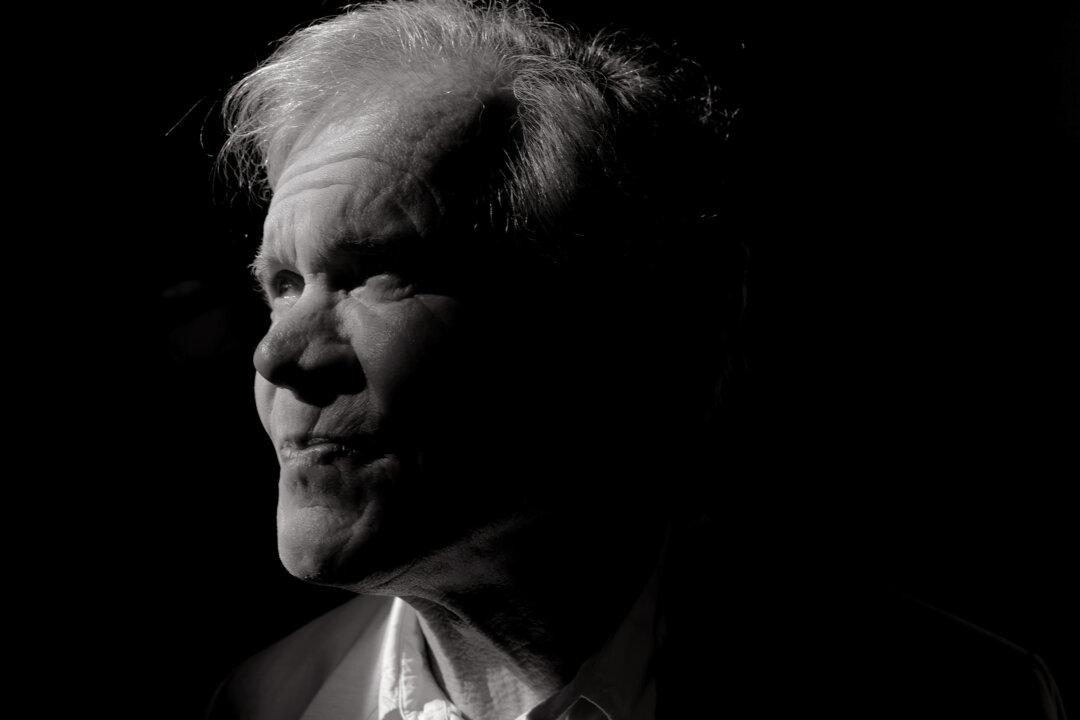

LOS ANGELES—Shaking hands with legendary adventurer Rick Ridgeway outside his serene Ojai home, I felt like I was meeting Indiana Jones—a comparison made by Rolling Stone—after he’d hung up the hat and whip.

LOS ANGELES—Shaking hands with legendary adventurer Rick Ridgeway outside his serene Ojai home, I felt like I was meeting Indiana Jones—a comparison made by Rolling Stone—after he’d hung up the hat and whip.