Can understanding classical art give us insights into our political relationship with the Middle East? Artist and scholar Stanley Bulbach believes so.

For Bulbach, who weaves flatwoven carpets, the phrase “classical art” expands in both aesthetic and historical meaning. This expanded view of classical art, he suggests, can challenge us to reconsider where Western civilization came from—back past the Greeks to ancient Mesopotamia, now modern-day Iraq, but traditionally called the Near East.

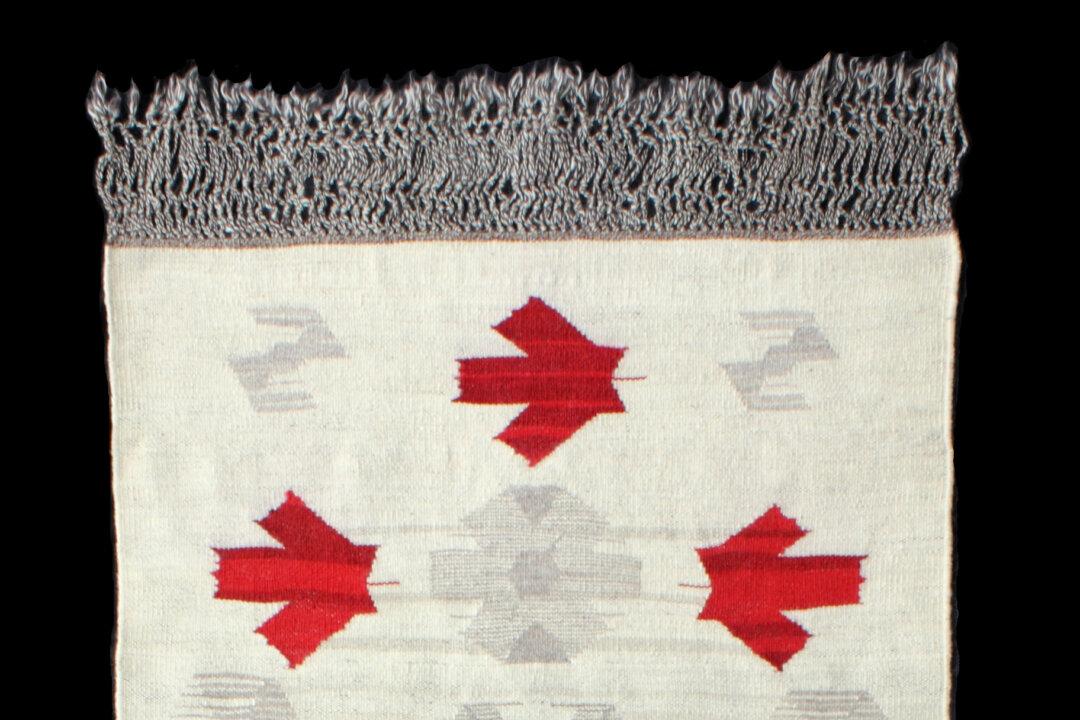

"September Passages," 2001, by Stanley Bulbach. A flying carpet. Courtesy of Stanley Bulbach