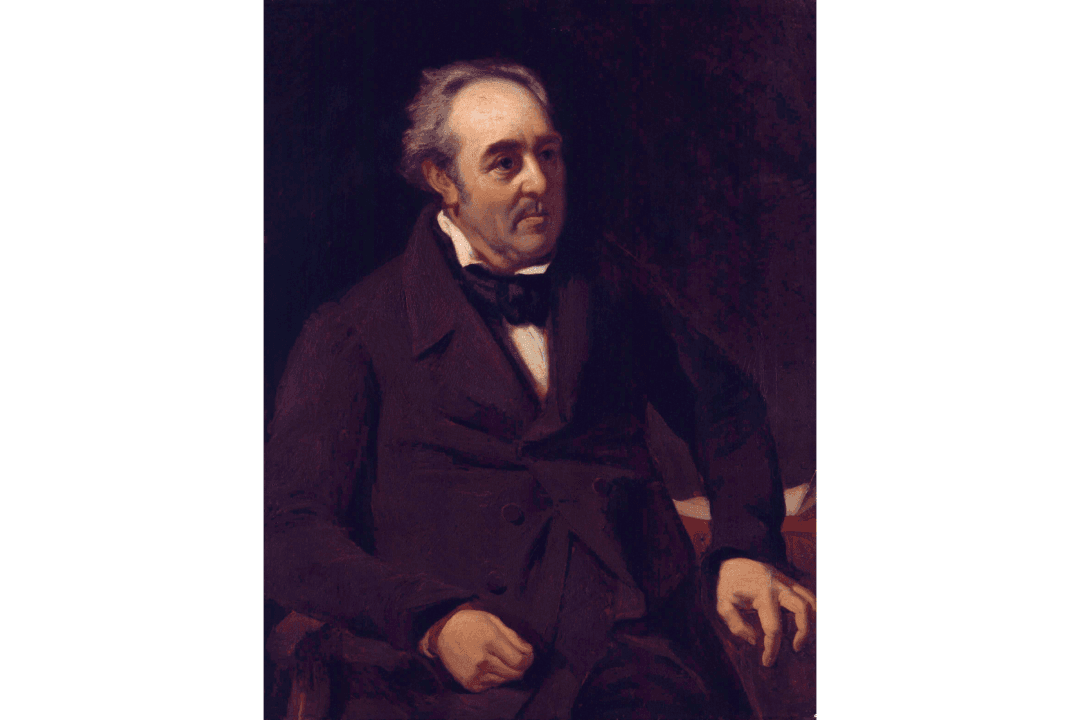

Many poets who don’t receive fame and praise during their life rise to popularity only after their death. Walter Savage Landor (1775–1864) had the opposite problem. During his life, he was a major influence on many of the poets known to us today, but Landor is little known now. One of the few places his work is found is in the anthology “Immortal Lyrics.”

Landor was best known for his epigrams, which are short, often witty poems that concisely convey a complex idea. He also wrote “Imaginary Conversations,” a series of dialogues between historical and mythological figures on moral, political, and philosophical topics. During his life, he counted many famous writers among his friends, including Charles Dickens, Robert Browning, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Charles Lamb. He is said to have influenced writers such as William Butler Yeats, Robert Frost, and Ezra Pound.