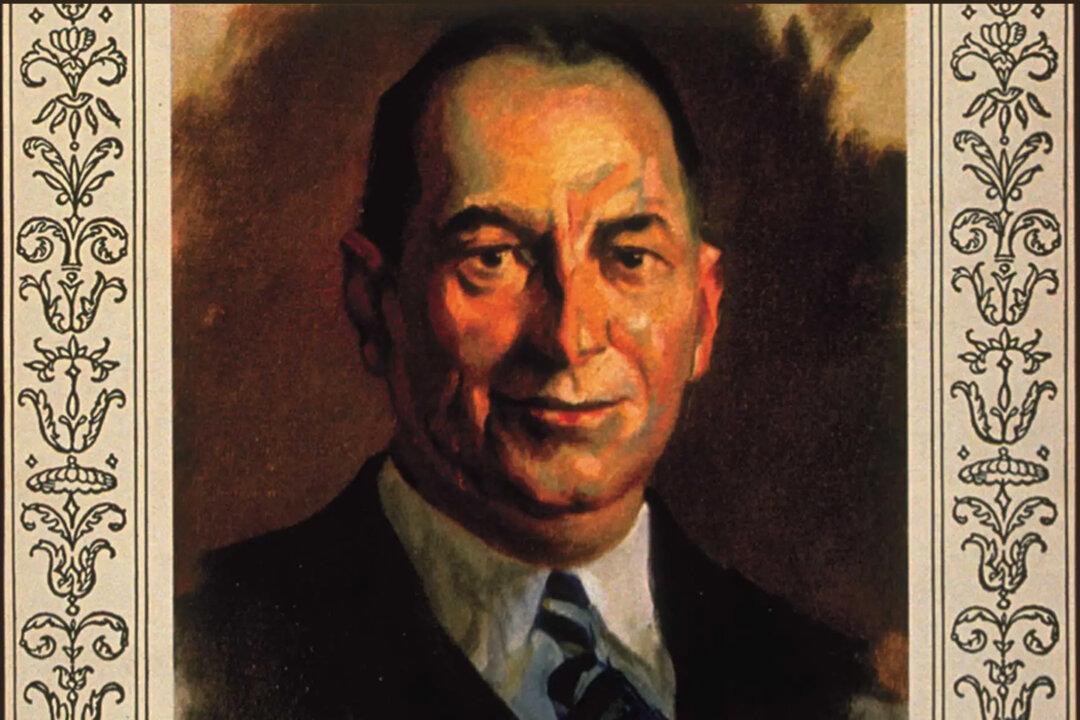

He was a wide-eyed young man infatuated by machinery. Throughout his life, his willingness to learn was his greatest schooling—his day school, his adult education program, his university.

A son of the bare plains of Kansas, Walter Chrysler refused to go to college after graduating from high school, dashing the hopes of his engineer father. Instead, he took a job in the Kansas engine yards as a sweeper for low-paying, workingman’s wages. In the process, he learned about the novel, integral machines which long fascinated him. After his apprenticeship ended, he bounced around to different railroad jobs in the West. Before long, he had learned enough to become master mechanic of the expansive Chicago Great Western Railway.