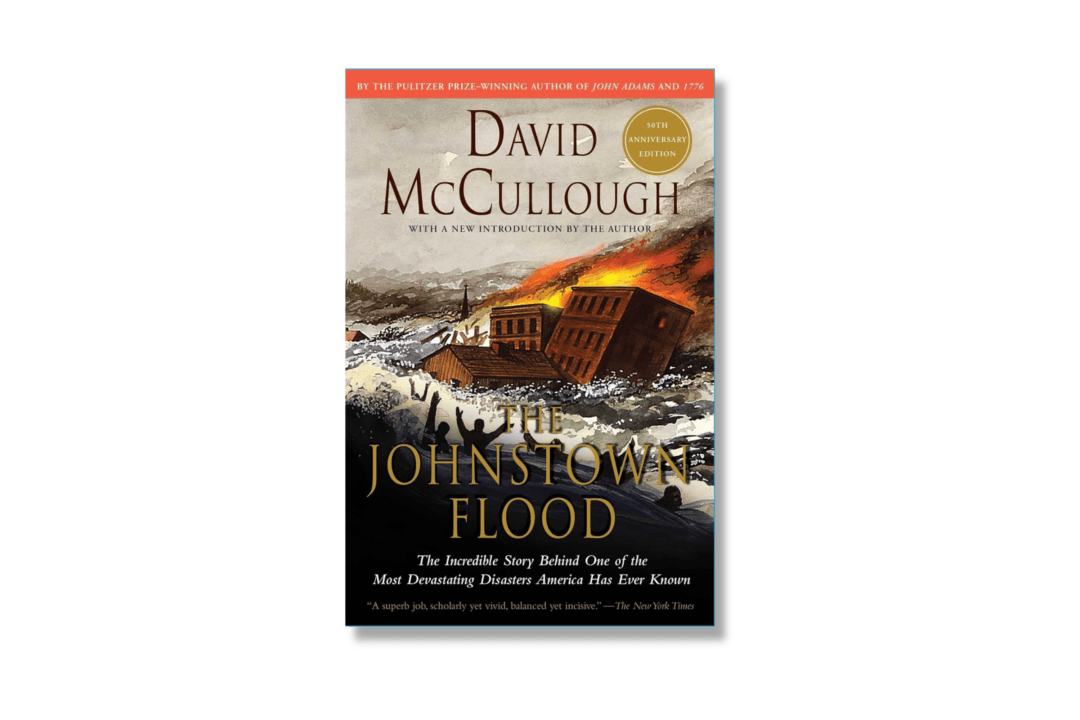

Millions of historian David McCullough’s books have been sold, with two garnering Pulitzer Prizes and some made into movies or included as Ken Burns’s documentary resources. Yet McCullough’s writing career began with a focus on a long-forgotten tragedy that nearly wiped out a small town 57 miles east of Pittsburgh.

The thorough volume “The Johnstown Flood” celebrated its 55-year history last year, with the famous author still discussing his debut work before he passed in 2022. As is the case with all McCullough books, mesmerizing details abound due to accurate and attentive research. The acknowledgment page informs readers that the author pored over innumerable newspaper clippings, first-person accounts, letters, diaries, court records, engineering reports, and more to gain a comprehensive as well as sensory understanding of the events that befell Johnstown, Pennsylvania, on May 31, 1889.