Lavinia “Vinnie” Ellen Ream (1847–1914), named after her mother, was the youngest of three children born to Robert and Lavinia in Madison, Wisconsin. Her father provided for his family as a land surveyor, though his ill health made it difficult to do so. Nonetheless, due to the demands of his job, the family occasionally moved, which was, at the time, no easy venture.

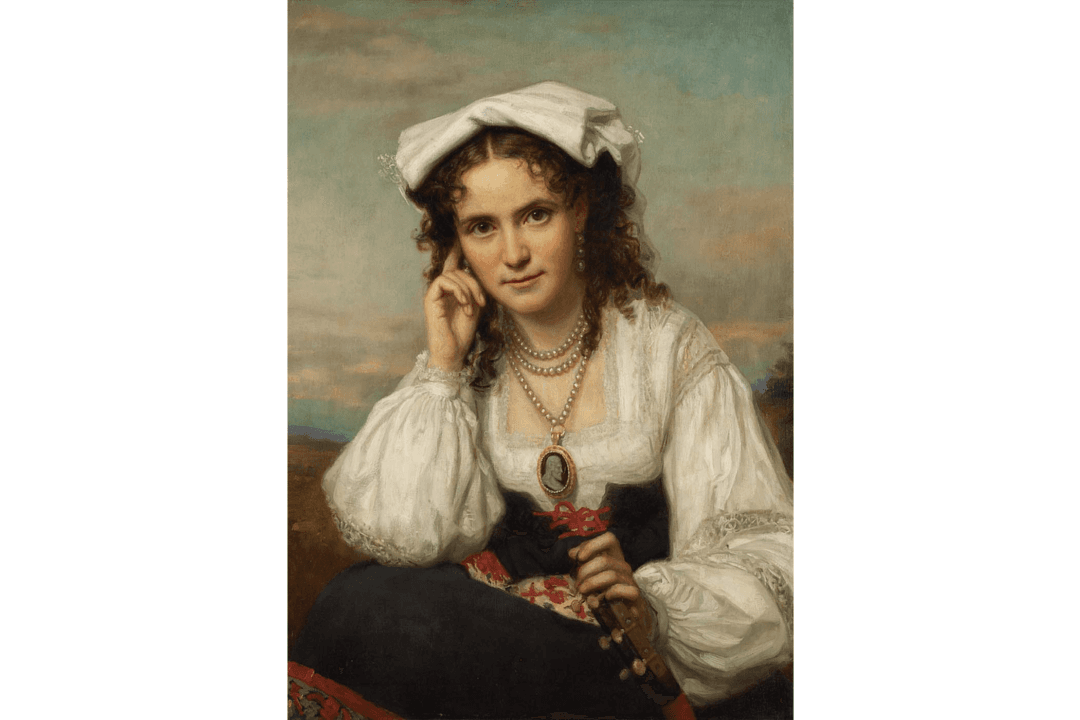

When the family moved to Kansas, Ream attended a local school across the Missouri River in St. Joseph, Missouri. After three years living along the Kansas-Missouri border, the family moved 145 miles east as the crow flies to Columbia, Missouri. It was here from 1857 to 1858 that she attended the all-girls Christian College (now Columbia College) and that her talents in music and art were first noticed. Her painting of Martha Washington still hangs in the St. Clair Hall, the school’s administrative building.