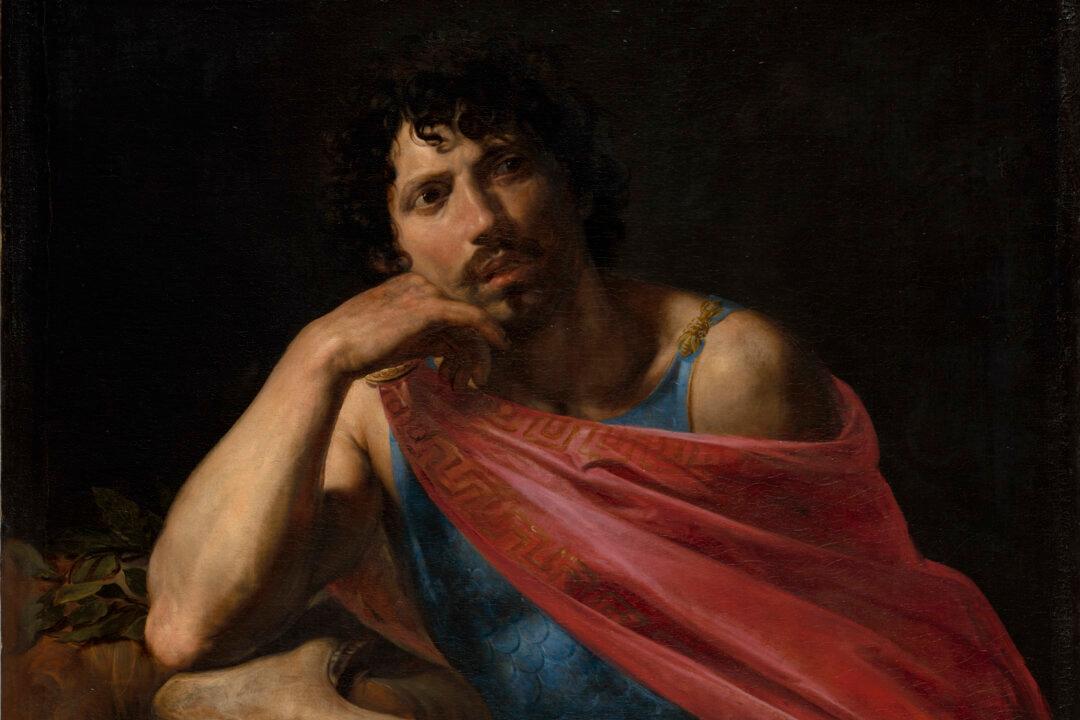

NEW YORK—Walk into the exhibition on Valentin de Boulogne at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and you risk being turned inside out or pulled into the midst of a Baroque drama. The paintings spew such emotive force that they can knock you about into sensory overload and then leave you in a state of intrigue.

“Valentin who?” you may ask. No, not Valentino, the heartthrob silent-screen actor, though Valentin de Boulogne’s paintings can draw you in like a movie. The artist was nicknamed “lover boy” by his confraternity, the Bentvueghels (Dutch for “birds of a feather”), who were Bacchus followers adept at debauchery. He died young, at 41, during a night of heavy drinking and a subsequent high fever in 1632.

Whatever his nickname may imply and despite the company he kept, Valentin received commissions from Rome’s most prominent patrons—Francesco Barberini (nephew of Pope Urban VIII) among them. Yet little is known about Valentin, which compels art historians to cling to every clue they come across.