Italian is the language of opera, and its opera roots are deeply planted in Europe. However, many operas have exotic settings, far beyond the countries where their composers and librettists lived or even visited. For example, Giacomo Puccini (1858–1924) wrote two grand operas with Asian settings. These two Italian operas are among the most famous classical works set in foreign lands. “Madama Butterfly” is set in Japan, and “Turandot” in China.

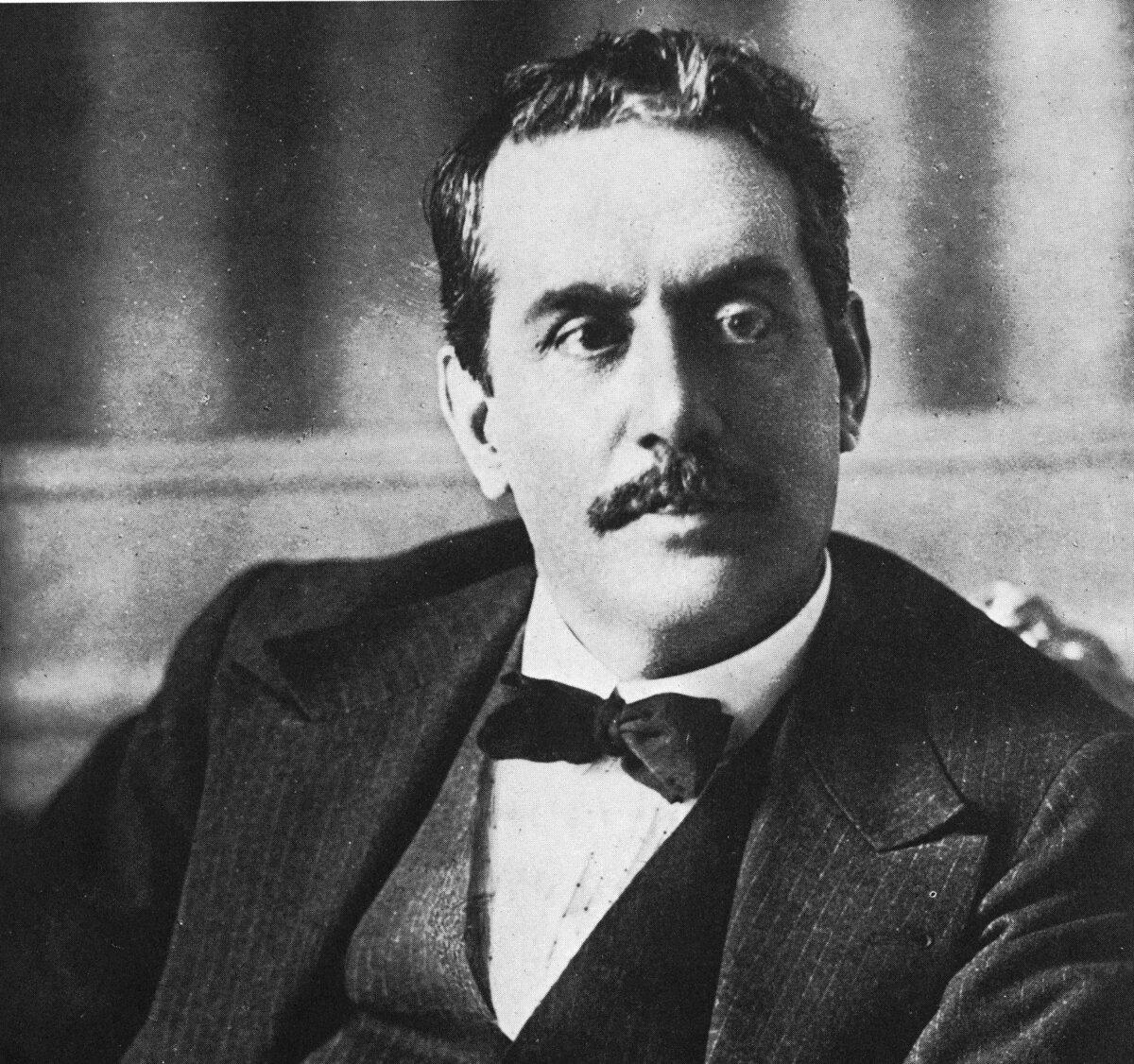

Italian operatic composer Giacomo Puccini, circa 1900. Puccini composed two operas, Madama Butterfly," and "Turandot," set in Asian countries. Kean Collection/Getty Images