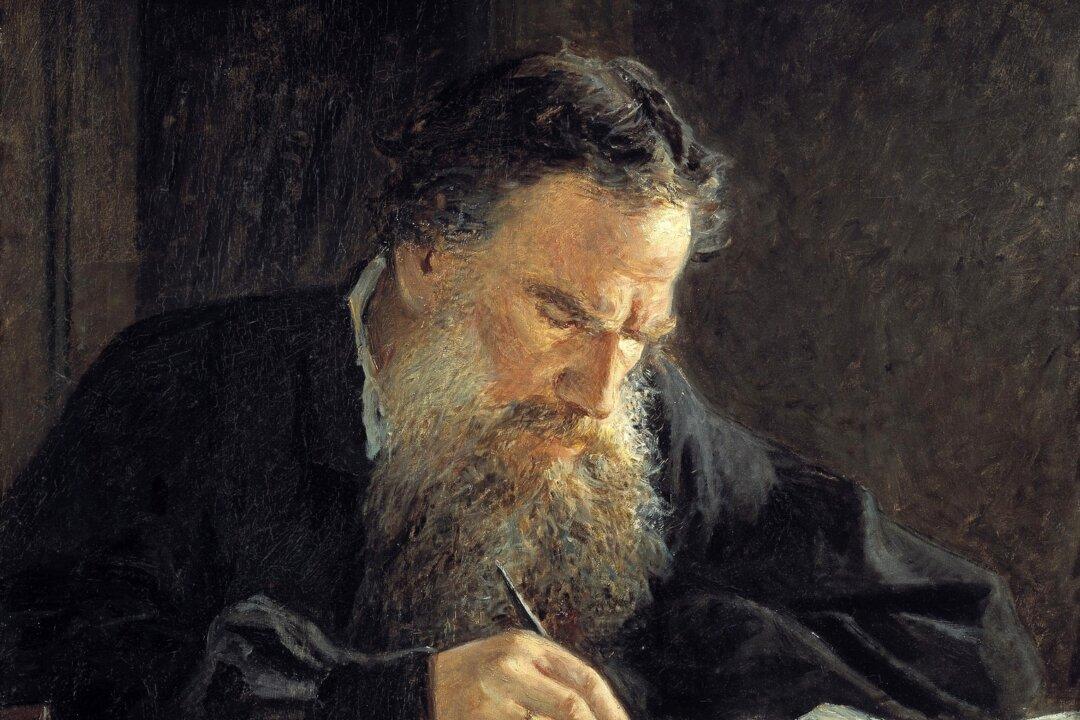

“The hero of my tale, whom I love with all the power of my soul, who is, was, and will ever be beautiful … is truth.” So wrote Tolstoy at the beginning of his creative life. On his deathbed, his last, unfinished sentence began with the word “Truth.”

To express the truth about man’s soul, to express those secrets that can’t be expressed by ordinary words, was, in his view, the task and the sole purpose of art. “Art is not a pleasure, a solace, or an amusement; art is a great matter. Only through the influence of art the peaceful cooperation of man will come about, and all violence will be set aside.”