The unparalleled events of George Washington’s life could fill half a dozen biographies of men with standard accomplishments. It is natural that his exploits as a revolutionary general and president would overshadow his early experiences in the French and Indian War. But without these initial achievements, the later ones would not have been possible. During this time, Washington trained and led the American Colonies’ first professional military unit: the Virginia Regiment.

Creating an Elite Fighting Force

During the Battle of the Monongahela, Washington had witnessed the devastating defeat of Gen. Braddock’s army and lived to tell about it, with four bullet holes in his coat as proof. He had seen neat rows of British soldiers fall to a smaller, unseen force of French and American Indians who fired muskets from behind rocks and trees. His experience convinced him that forest-fighting methods were more appropriate to the American terrain than European ones. After becoming a national hero as one of the only surviving officers of the Braddock Expedition, Col. Washington was named the supreme commander of Virginia’s colonial forces in 1755. He was only 23 years old.

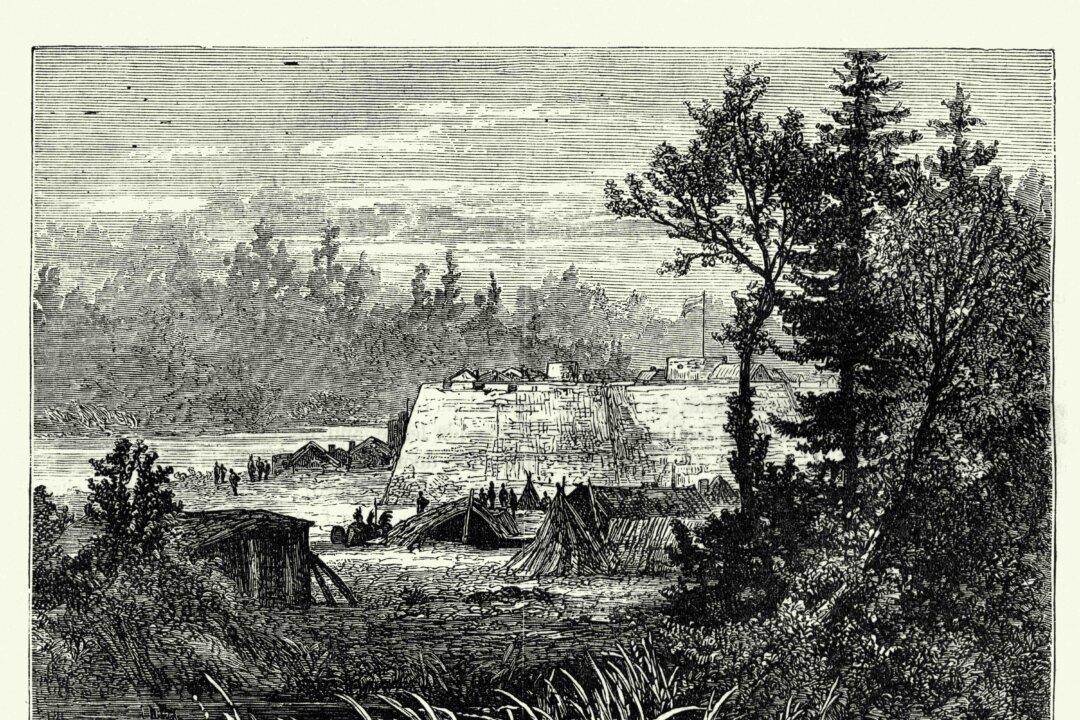

The frontier had become a savage place to seek a meager fortune. American Indian war parties regularly emerged from the wilderness to terrorize settlers, then vanished as quickly as they came, leaving chaos in their wake. “Every day,” wrote Washington, “we have accounts of such cruelties and barbarities as are shocking to human nature. … No road is safe.” He was tasked with protecting Virginia’s nearly indefensible 350-mile western border, and he knew that his only chance of success was training his men to fight like American Indians.

Washington was given the authority to recruit troops for the newly created Virginia Regiment. He oversaw both officers and a few hundred men conscripted from along the border. These poor pioneers tested him as much as his invisible enemies. The men were insolent and mutinous. Factions formed among those he called “indolent” officers, incited by a captain who refused to obey orders. Acting governor Dinwiddie blamed Washington for the anarchy, and ambitious men envious of his position slandered him in print. Virginia’s House of Burgesses initially hesitated to pass laws for enforcing obedience and gave him insufficient resources.