Disclaimer: This article was published in 2023. Some information may no longer be current.

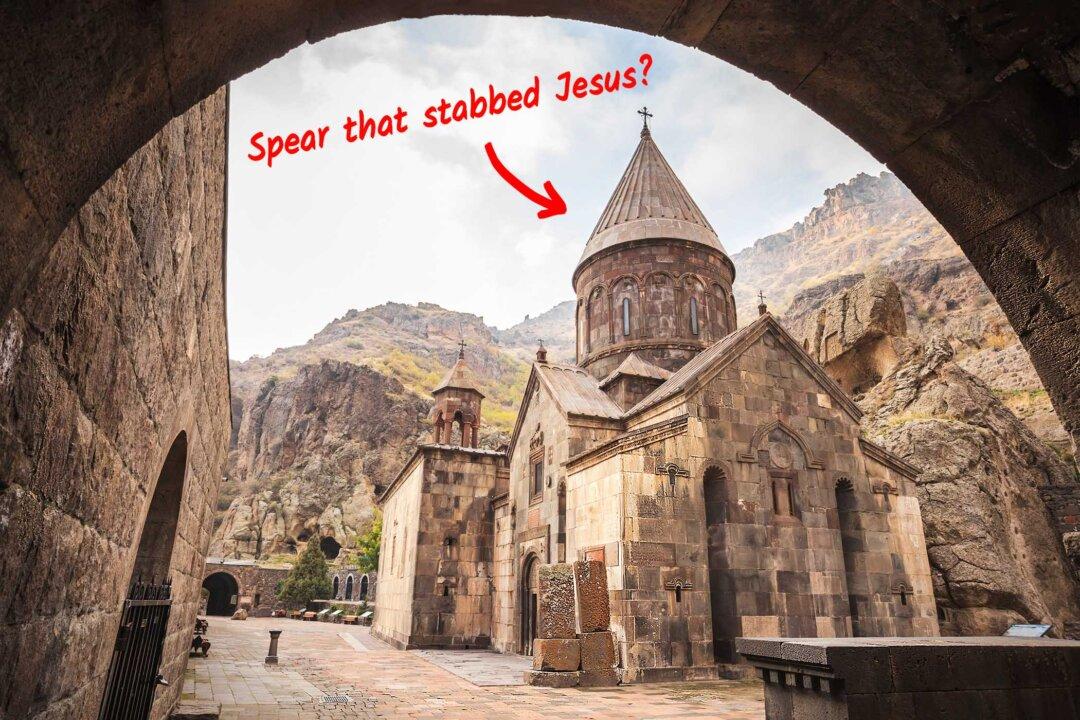

They had to make sure He was dead. That’s why the Roman centurion Longinus was called upon to raise his spear and pierce the side of Jesus as He hung on the cross on the night of His crucifixion, so the Bible says. It immediately drew blood and water, according to John. We are told how Jesus was entombed—and rose again on His journey to Heaven—yet that spear went on a different journey.