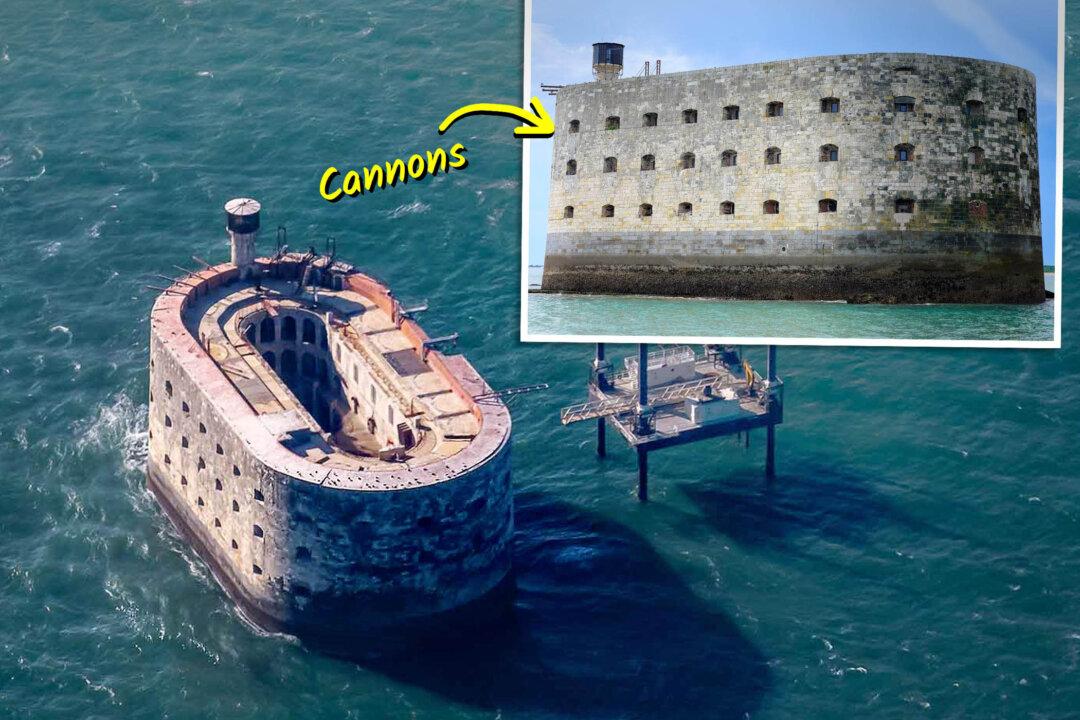

Before the days of hypersonic missiles, Old World kings and emperors built castles on the open seas.

Such fortresses make no sense strategically today. But centuries ago, stacking thousands of tons of stone on artificial reefs made perfect sense, though sometimes it was nearly impossible to accomplish. As for why they were so crucial along the coasts in places like 17th-century France, the answer can be summed up in a word: cannons.