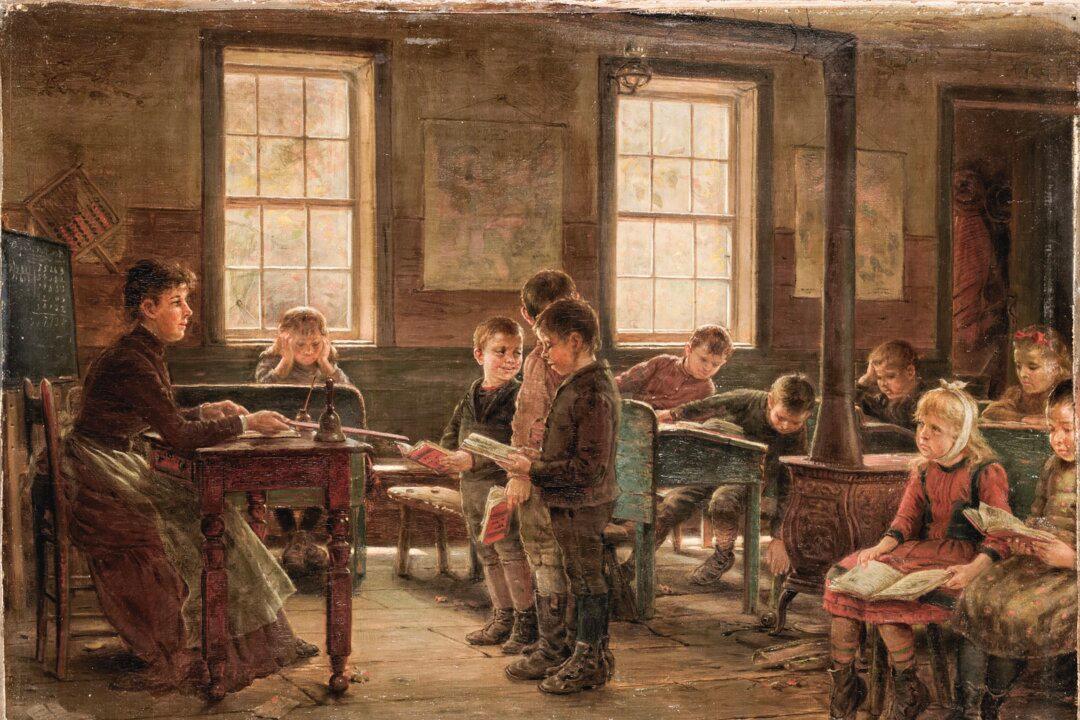

Small clapboard buildings, often painted white or red. Pot-bellied stoves. Blackboards and chalk, slate tablets and ink wells. McGuffey Readers and recitations. Dunce caps and hickory switches. Bespectacled schoolmarms. Calicoed girls with pigtails and tousled, mischievous boys.

Blend these images together and most likely a one-room schoolhouse pops to mind. Some of us may have never personally stepped foot in one of these buildings, but they appear in Western movies, in television shows like “Little House on the Prairie,” and in novels ranging from Mark Twain’s “Tom Sawyer” to Catherine Marshall’s “Christy.” They’re part of Americana, and we know them.