Theodore Maiman (1927–2007) was born in sunny Los Angeles, but grew up in the chilly mountain air of Denver. His father, Abraham, was an electronics engineer for Bell Laboratories, a career Maiman took great interest in. As his father built an electronics laboratory wherever they lived, Maiman quickly became experienced in fixing and building electronics. By the age of 12, he received his first job at an electronic appliance shop. Two years later, he was running the repair section of the store.

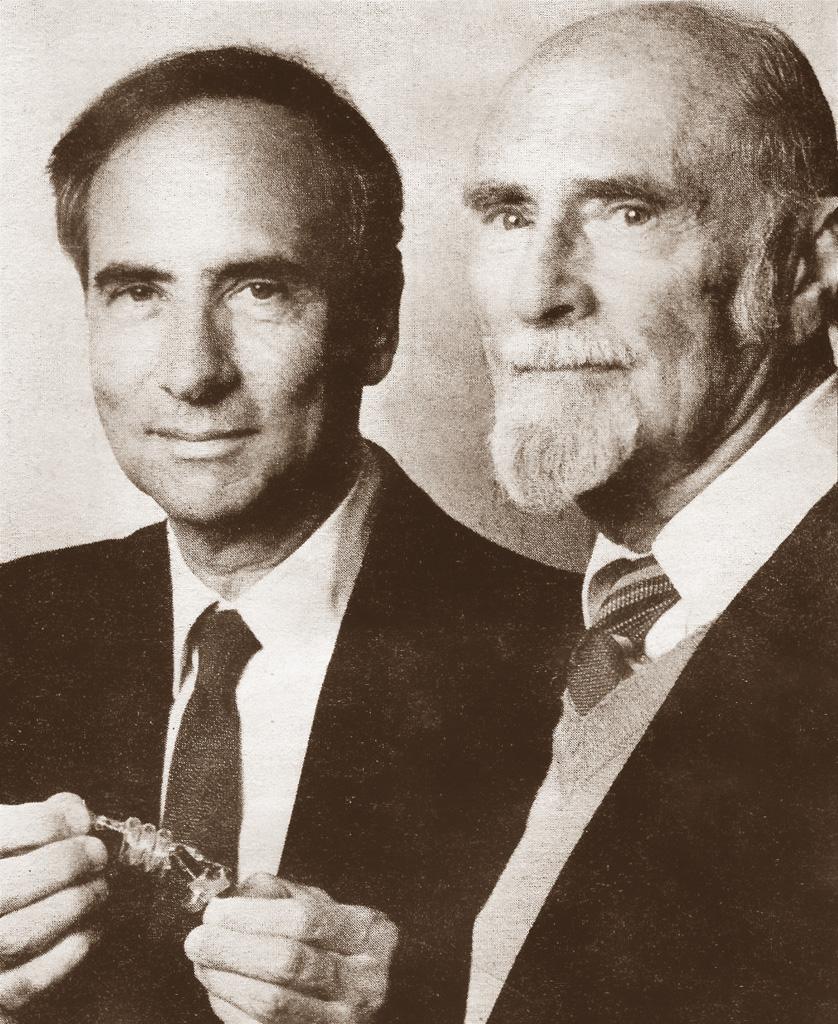

Theodore Maiman with his father, Abe (circa 1987), who encouraged his interest in electronics. BolkoR/CC BY-SA 4.0