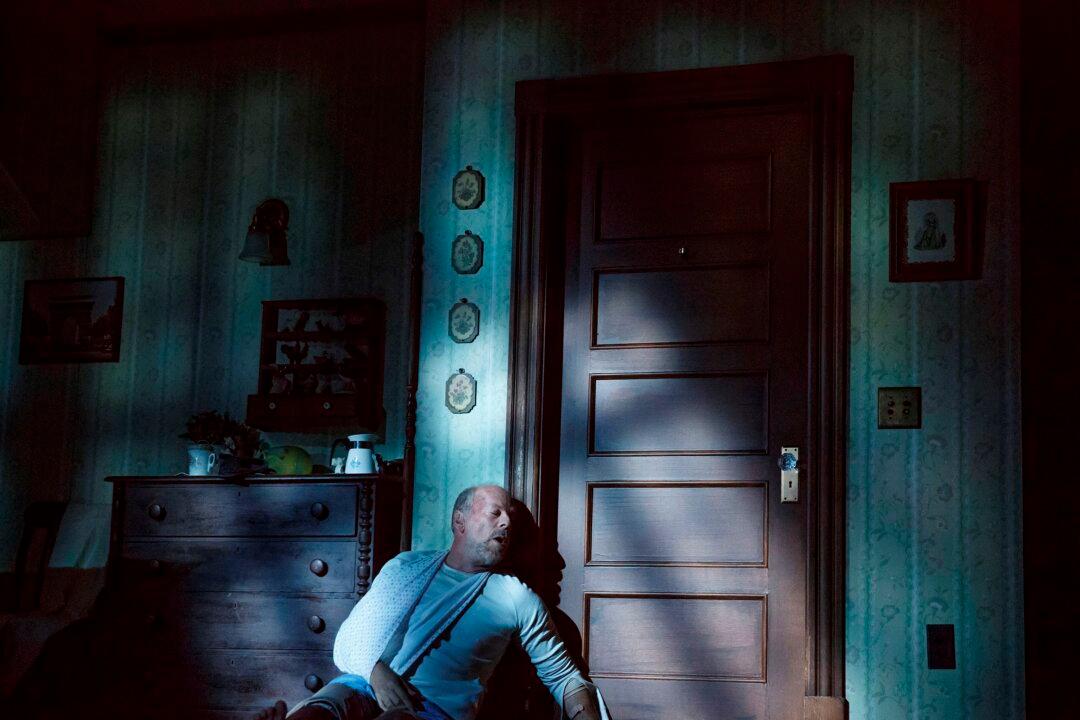

NEW YORK—In a world in which insanity encroaches on us, it’s good to be reminded once in a while that we have more strength than we might believe. The Broadway thriller “Misery,” a stage adaptation of Stephen King’s novel of the same name, taps into that strength as well as the fear of being alone, helpless, and dependent on the kindness of a stranger.

In this case, the stranger might shower you with praise one moment and attempt to kill you the next. The work is truly terrifying at moments but fails to keep the intensity throughout.

'Misery' is a roller coaster of a thrill ride, where only the most determined survive.