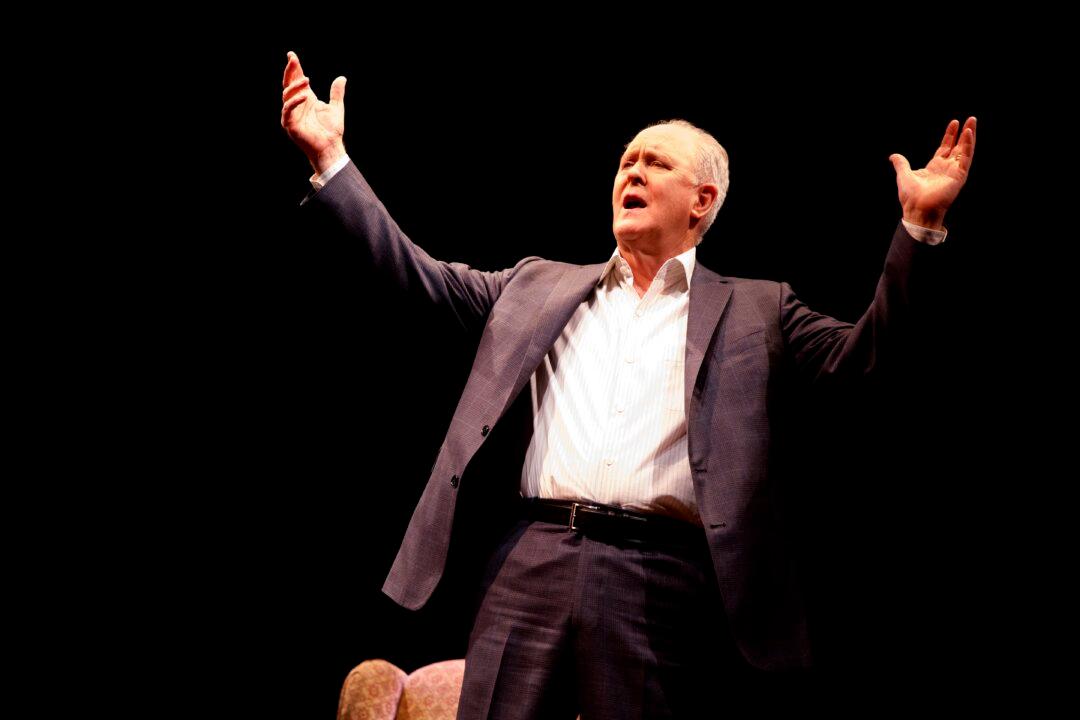

NEW YORK—All theater tells stories and all actors are storytellers notes John Lithgow in his one-man Broadway show “Stories by Heart.” Lithgow, in an absolutely sterling performance, uses the classic art of storytelling to take the audience on a journey through his own past, while also showing just how transformative the power of the spoken word can be.

Stories have a special place in Lithgow’s heart thanks to his father, Arthur Lithgow. An actor, producer, director, and teacher, he is the main reason his son became an actor himself. Particularly enamored with Shakespeare, the elder Lithgow founded a number of theater festivals over the years, including The Great Lakes Theatre Festival, which is still going strong today.