While Kenneth Grahame’s novel for children “The Wind in the Willows” is in many ways a love letter to home, it also points out a tension between our love for home and our need for pilgrimage. As much as it benefits us to have community, we also benefit from seeking new places and people. The story affirms the benefit of travel and adventure, but with a caveat: Like all good things, adventures are to be had in moderation.

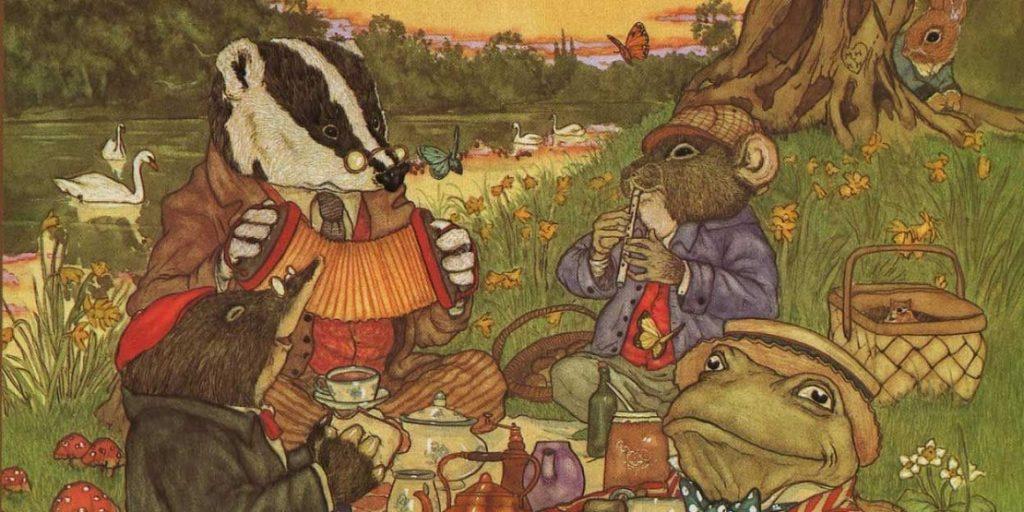

Published in 1908, “The Wind in the Willows” follows the adventures of Mole, Rat, Badger, and Toad, all of whom have widely varying relationships to home and different levels of yearning for adventure. Much of the novel follows Toad’s escapades as his friends try to help him rein in his wild and reckless pursuit of adventure. In Toad particularly, we see the love of adventure taken to its excess and the need for stability and a stronger tie to home. By contrast, Mole is the example of an animal who grows as a character and benefits from emerging from his mole hole into the outside world, as we all are sometimes called to do.