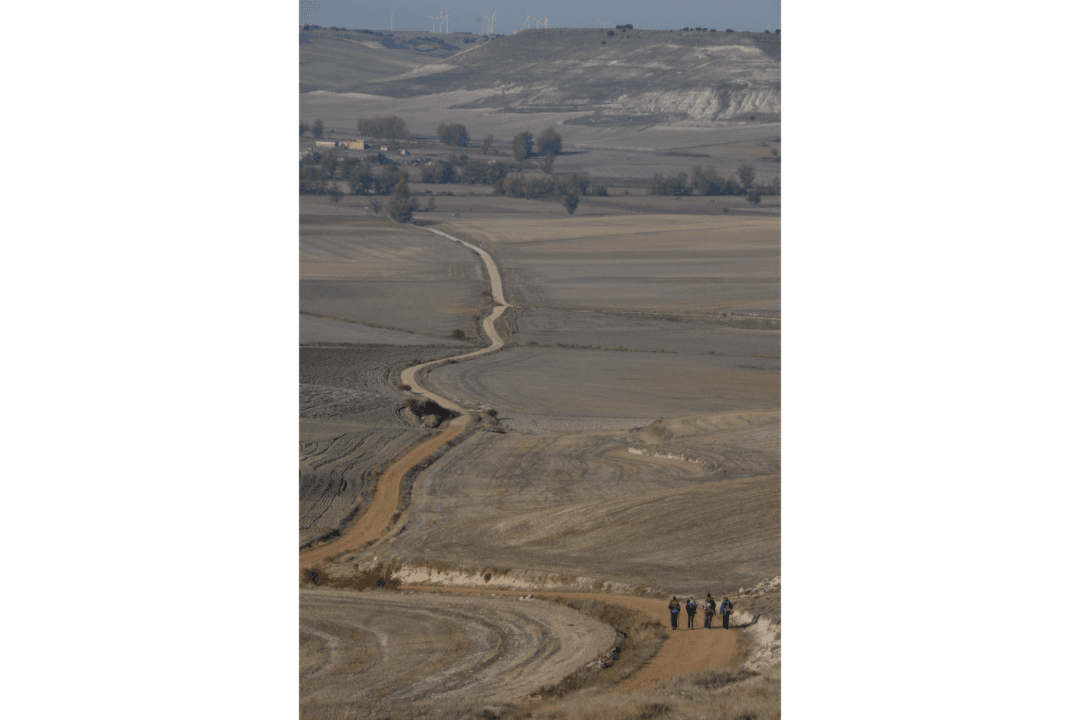

Real-life father and son Martin Sheen and Emilio Estevez star in this film about Thomas Avery (Sheen), a respected ophthalmologist, who wishes that his adult son Daniel (Estevez), was more worldly. They’ve grown apart, but when Daniel dies while on a Christian pilgrimage in Europe, a shattered Avery rushes there. A nonbeliever, he just wants to be done with the personal duties of recovering or cremating the body and rushing back to his professional duties.

Martin Sheen (L) and Emilio Estevez on the set of "The Way." Icon Entertainment