The question pulls at the mind as tight as a stretched canvas: Given his legacy as an exceptional painter, art theorist, and founding member of the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, why is Charles Le Brun (1619–1690) not given attention on par with Nicolas Poussin or Peter Paul Rubens?

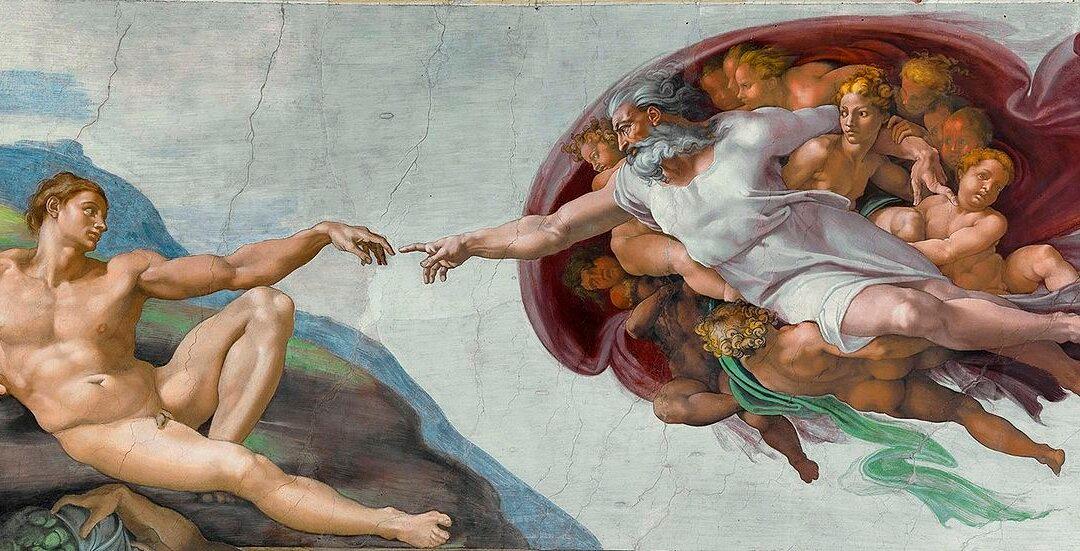

Anyone in love with the rich paintings of Baroque art will inevitably engage with its grand masters such as Poussin, Rubens, or Anthony van Dyck. Vast numbers of exhibitions, publications, and even films have shaped our perception of biblical and mythological scenes, further branding these scenes into our collective consciousness.