There’s something about the creative process that is intriguing, especially to non-artists. Stories about writers, composers, and artists are popular subject matter for literature and the theater. Several operas are based on these creative individuals.

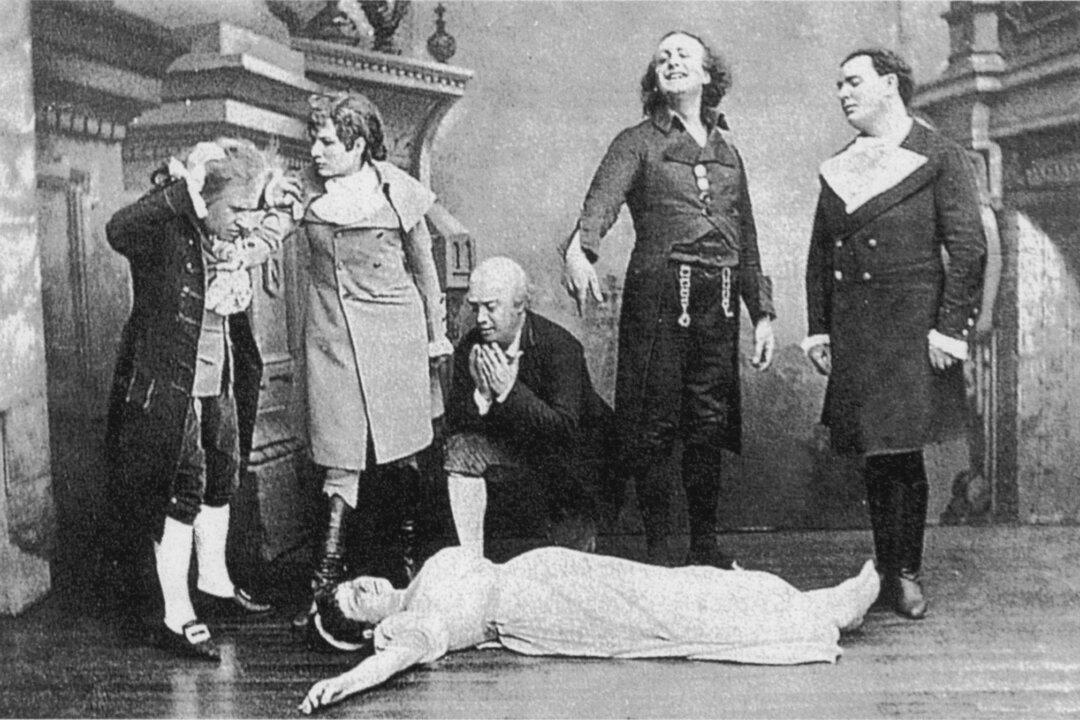

Jacques Offenbach (1819–80) based his French opera “The Tales of Hoffmann” (“Les Contes d’Hoffmann”) on the life of German author E.T.A. Hoffmann (1776–1822). Jules Barbier wrote the libretto and co-wrote the 1851 play on which it was based, “Les contes fantastiques d’Hoffmann,” with Michel Carré.