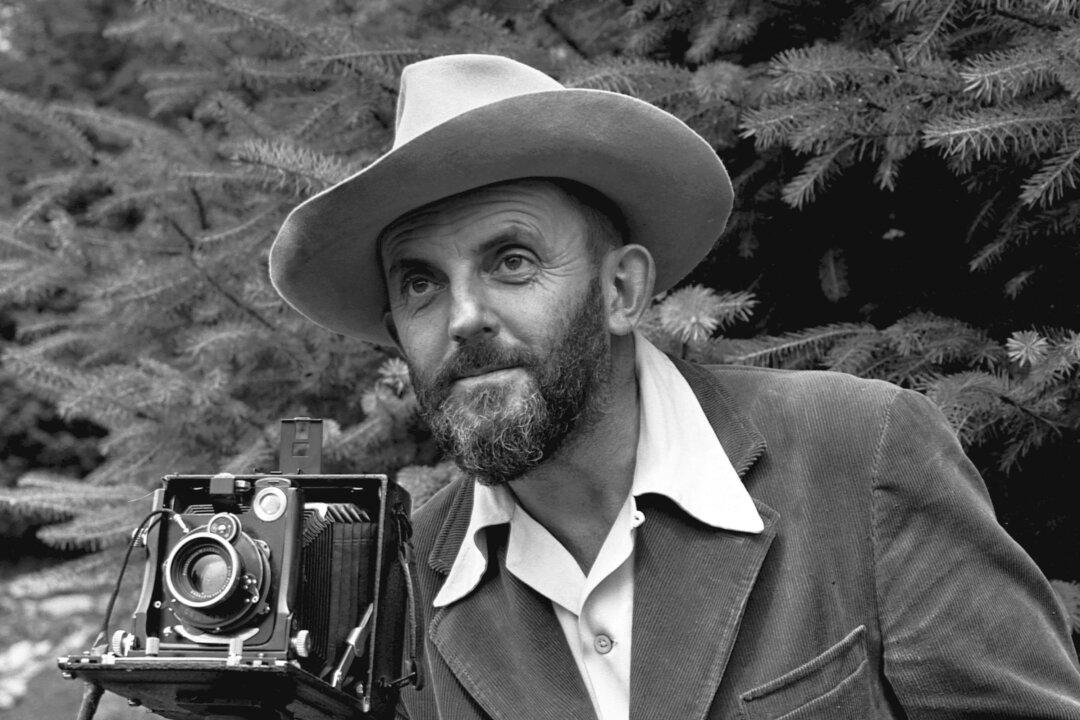

Ansel Adams’s bold, black-and-white landscapes of the American wilderness are so iconic that most people know an Adams photograph when they see it.

You might be surprised to learn that Adams didn’t learn his craft by attending an elite art institution or by apprenticing with a master photographer.