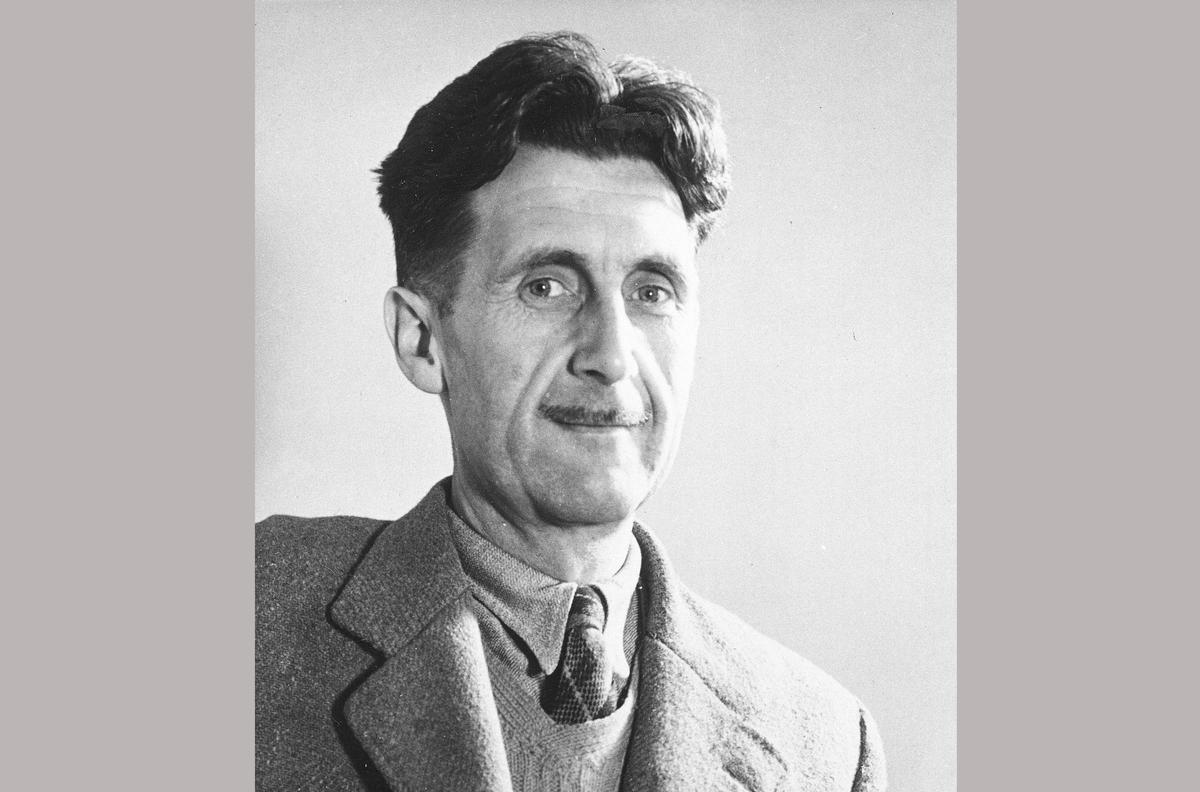

“The secret of his style is its invisibility,” British critic John Carey wrote in 2003. He had in mind a writer who had composed “the most vibrant, surprising prose of the 20th century, but disguised it as ordinary talk.” His writer’s name was Eric Arthur Blair, otherwise known as George Orwell.

George Orwell, author of "1984." AP Photo