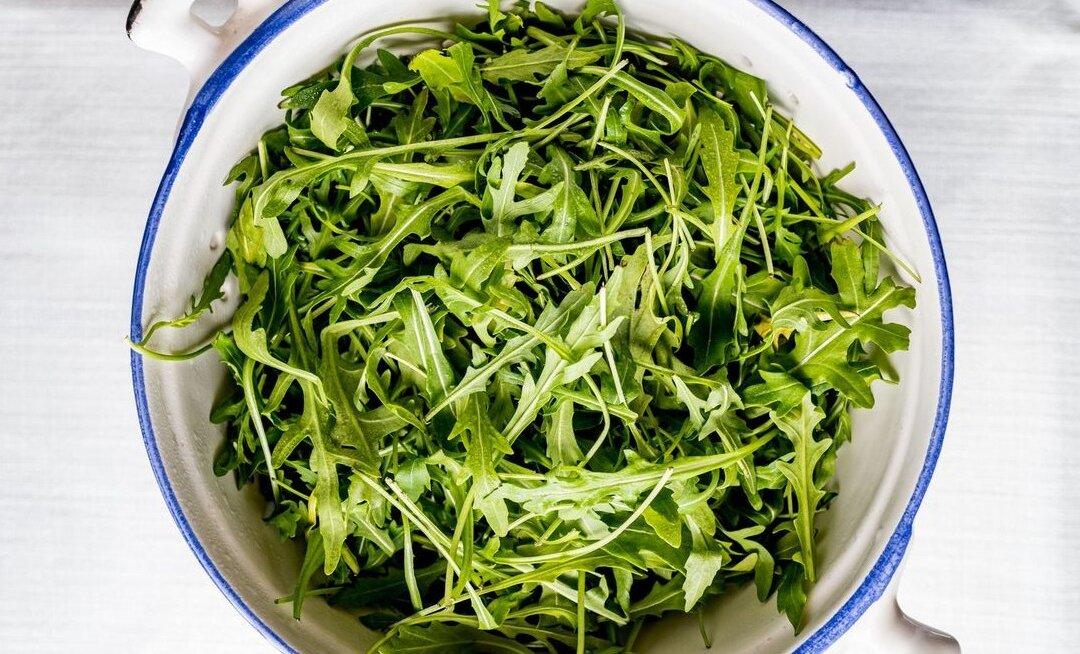

These days are made for ragù. It is cold outside, and the windows in your kitchen will quickly be fogged up by the steam from the pot of meat sauce sputtering on the stove. The smell, that familiar, heartwarming, delicious aroma, will stick to your clothes like the warmth of your grandma’s hug.

I grew up eating my grandma’s Tuscan ragù, something she would make to celebrate our Sunday family gatherings. In the past, the hearty meat sauce was reserved for only holidays or special occasions, such as days of threshing or harvesting.