G | 1h 30min | Drama | 1993

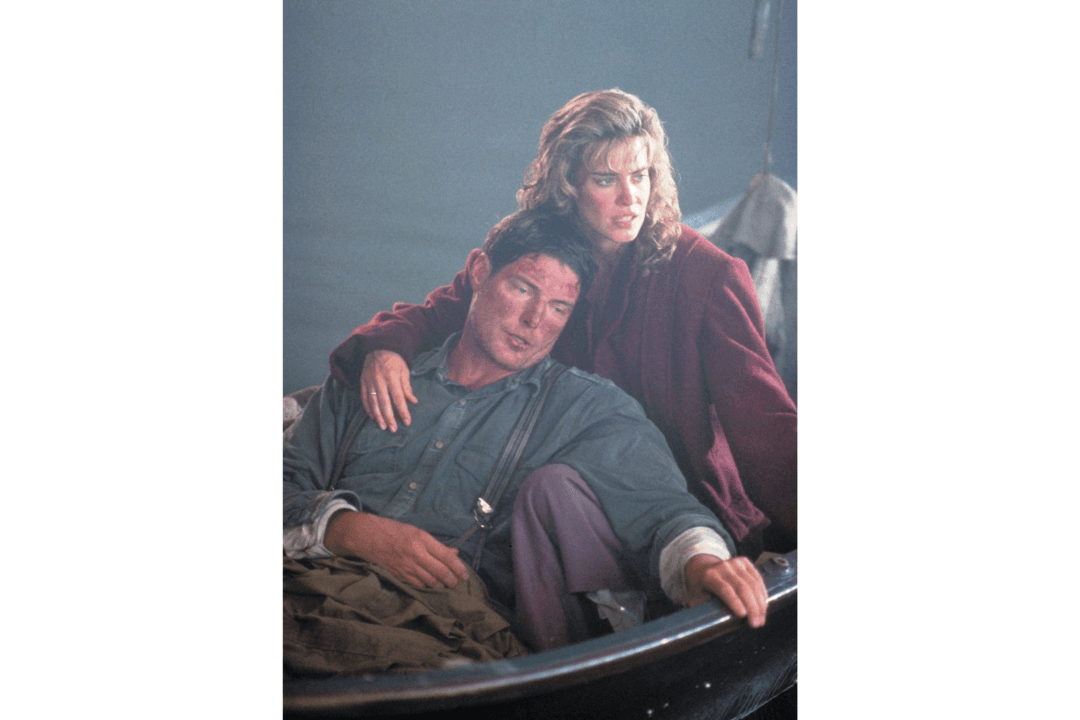

Director Michael Anderson’s film ponders the inner battle between a reckless conviction that believes that man is no more than a beast and a responsible one that corrects him: He’s human. No more, but certainly no less.

G | 1h 30min | Drama | 1993

Director Michael Anderson’s film ponders the inner battle between a reckless conviction that believes that man is no more than a beast and a responsible one that corrects him: He’s human. No more, but certainly no less.