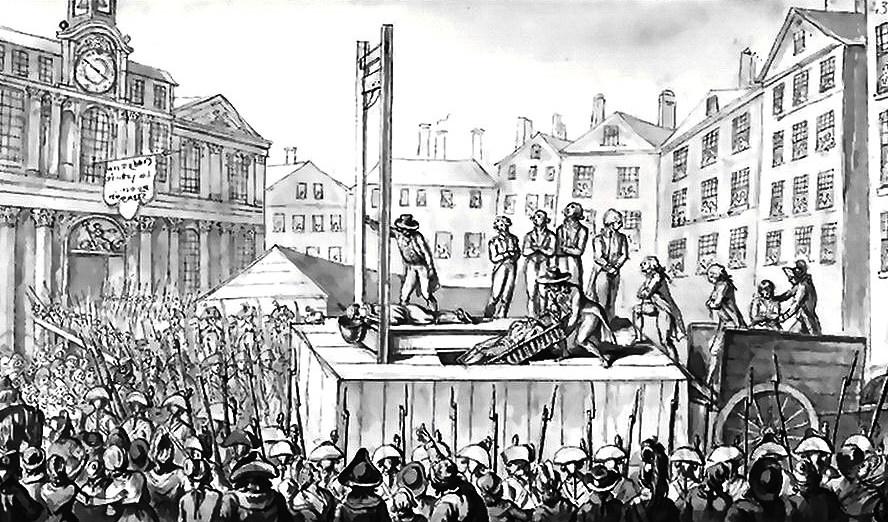

What does the Reign of Terror during the French Revolution have in common with the witch hunts in Europe? More than you might think. It’s interesting that in our current climate with its wide cultural gap, “conservatives” denounce the Terror and “progressives” excoriate witch hunts. Yet, while apart in time and place, the events are eminently comparable.

Before getting deep into this, a little history refresher is in order. By “witch hunts,” I‘ll be referring to the European witch hunts, events that occurred mostly in the 15th through 17th centuries. The European witch hunts in general, or the question of Satanism, is too large a topic to address in one article, but I’ll focus on one set of witch hunts: the North Berwick Witch Trials that took place in Scotland in 1590. These trials are a good example of the whole three centuries identified by scholars as the European “witch craze.” They are a good example because just as in almost all the other witch hunts, the roughly 70 victims were killed not by mobs but by the legal process itself.