Some say that one man’s industrial invention gave rise to the slang idiom “the real McCoy,” a turn of phrase denoting quality and authenticity. Although most commonly accepted accounts of the phrase state otherwise, the true origin of the expression matters little: A uniquely American tale can to be told from one of the popular interpretations.

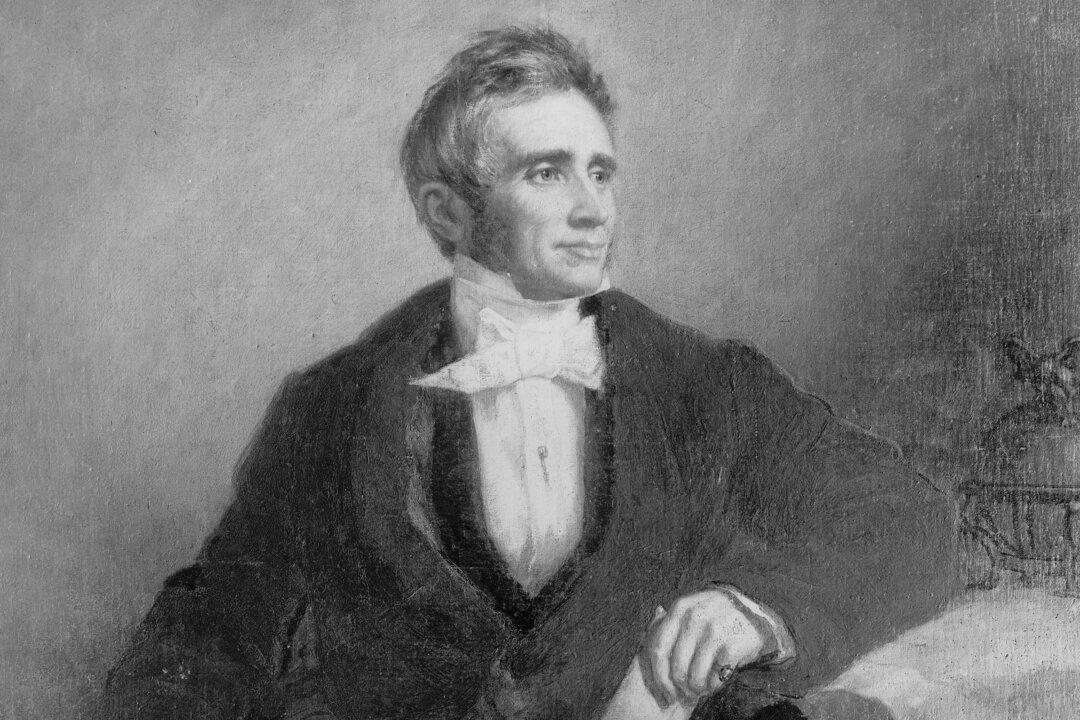

Elijah McCoy was a prolific inventor with prodigious mind, patenting an impressive array of devices, approximately 50 to 75 total (sources range between the two figures). Indeed, McCoy was a pivotal player in the development of lubricating systems for the industry and transportation systems of the 1870s, as the economy of coal, corn, wheat, and railroad shipping exponentially matured in America.