“The establishment of our new Government seemed to be the last great experiment for promoting human happiness, by reasonable compact, in civil Society.”

—George Washington, in a letter to Catharine Sawbridge Macaulay Graham, Jan. 9, 1790

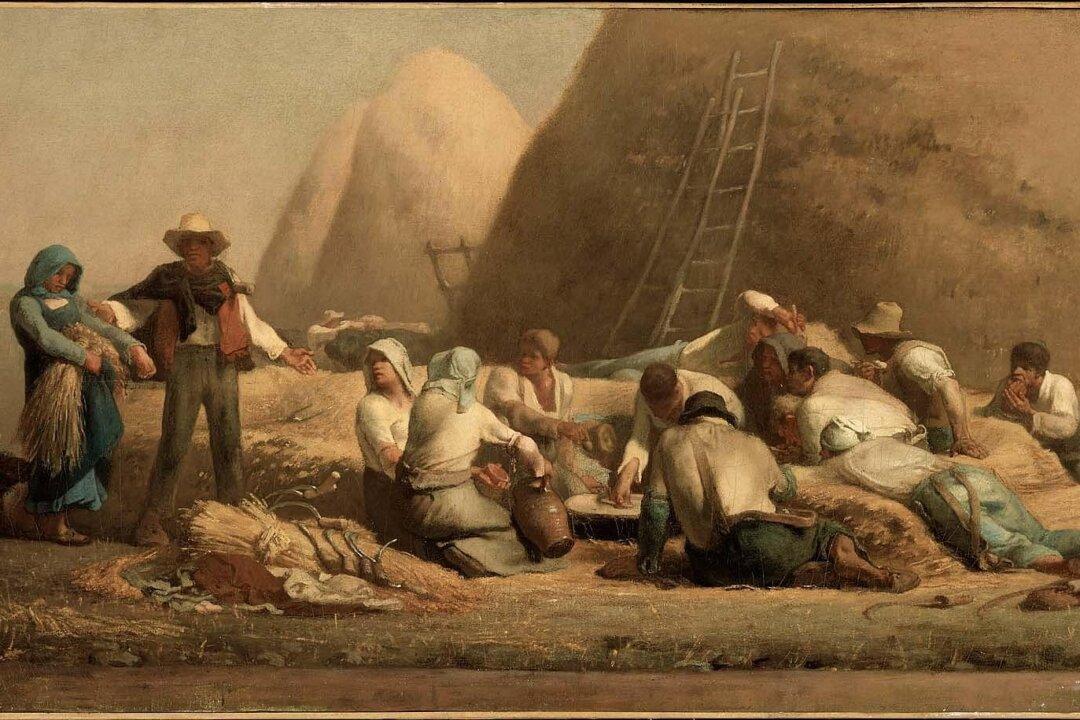

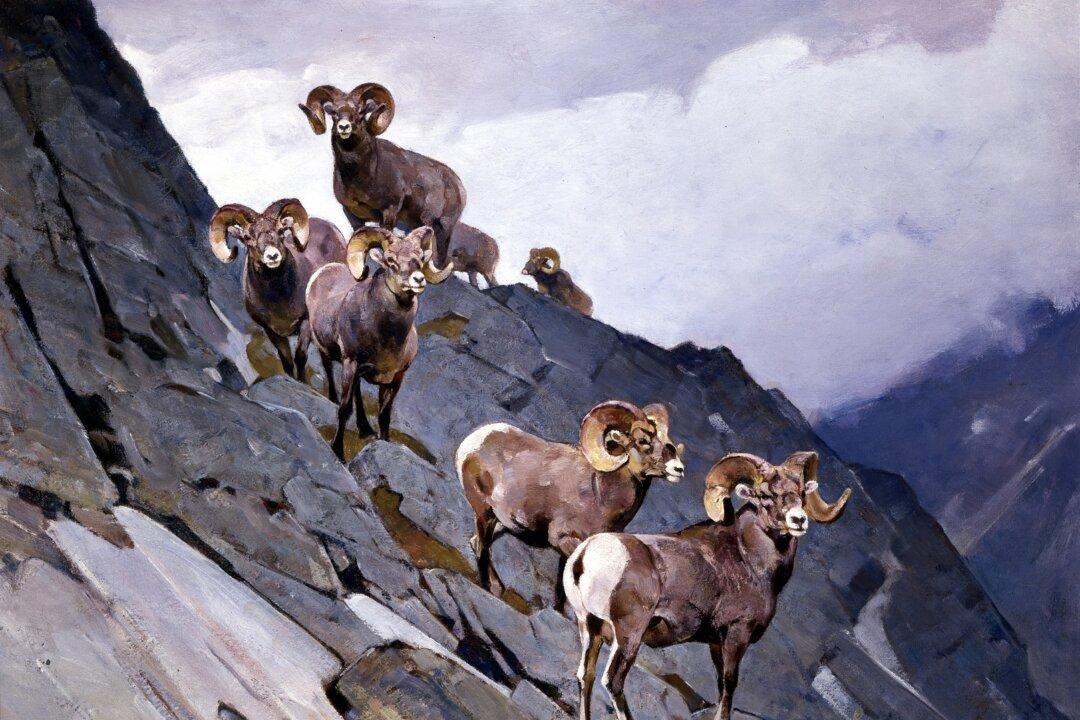

We’re living in the Great Experiment. Established less than 250 years ago, the United States is founded on the revolutionary conviction that independence, hard work, and honor can bear great fruit. Americans benefit from a prosperous legacy of faith, hope, and grit. The treasures of our heritage are a gift that each generation has the power to squander or save.