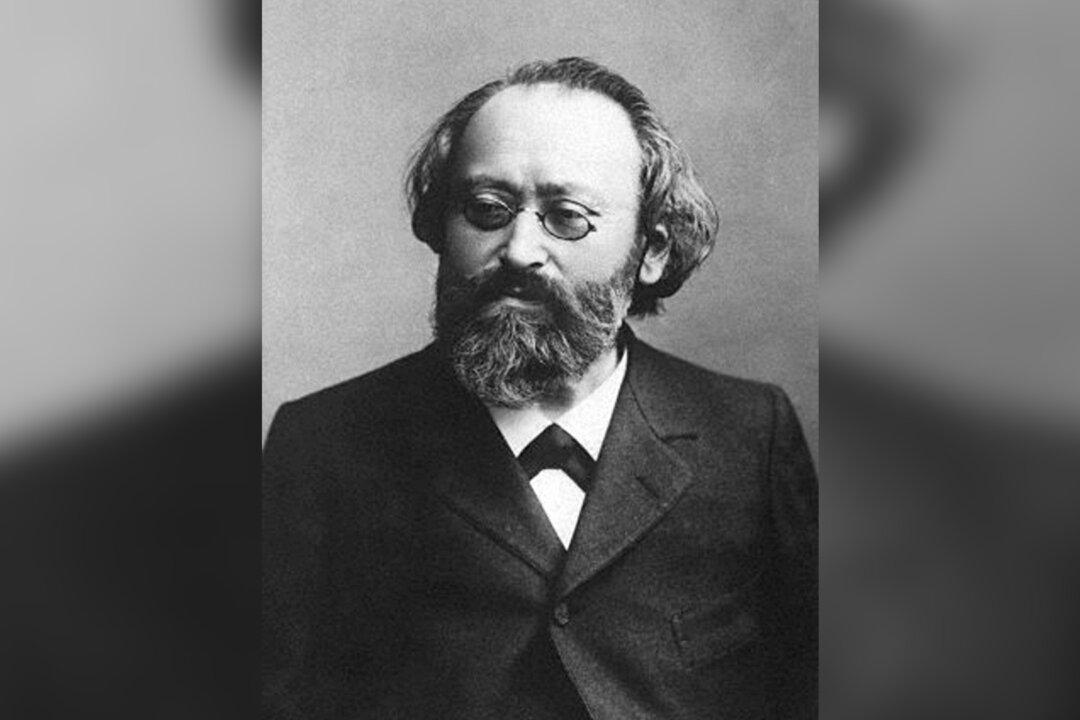

If a fourth ‘B’ were added to the list of great composers—Bach, Beethoven, Brahms—Bruch would probably be it. Many classical music aficionados are familiar with Max Bruch for his first violin concerto. It is a standard of the repertoire, one of the most frequently performed works in that form, and justly so.

In Bruch’s own lifetime, however, his status loomed large for different reasons. A late 19th-century collection of biographical sketches, “Famous Composers and their Works” by J.B. Millet, included Bruch’s name within its pages during his lifetime. It began by mentioning his concertos and symphonic works, then pronounced the judgment that “it is upon his great choruses that his fame as a composer, and his right to admission to the ranks of the masters, chiefly rests.” The six-page biographical entry concludes with a list of his most important compositions that names some of these oratorios, operas, and songs.