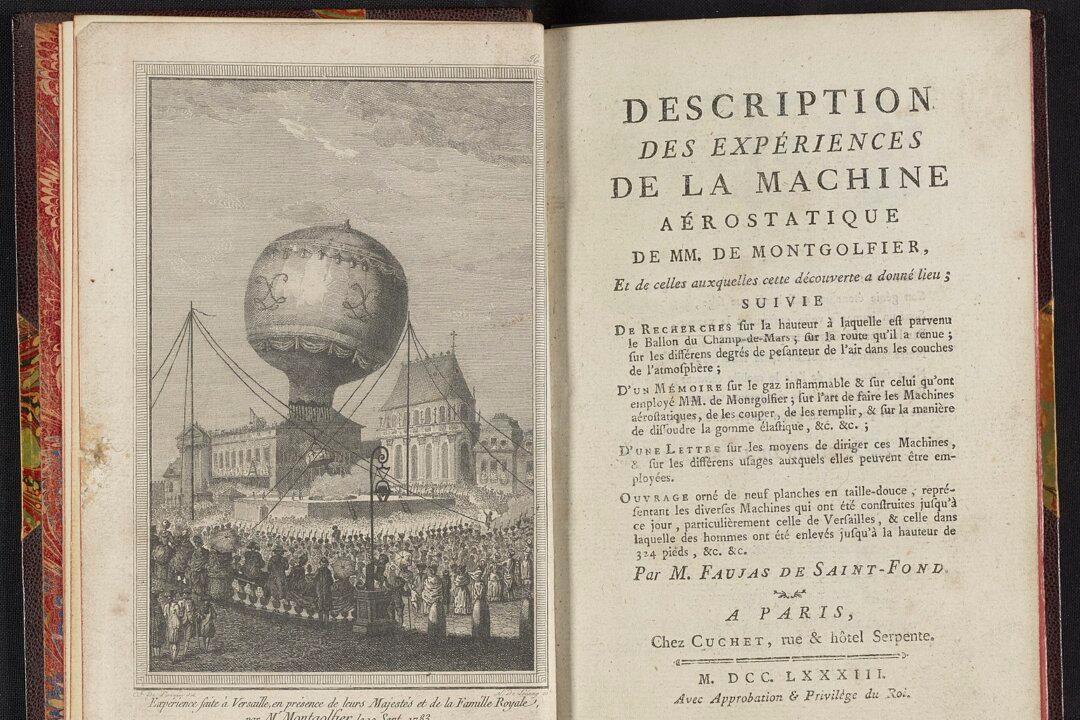

What was the first living creature to fly in a manmade contraption? It wasn’t a monkey. It wasn’t a dog. It certainly wasn’t a human. It was an unlikely trio of animals, actually: a sheep, a chicken, and a duck, and they were flung aloft by a pair of enterprising French brothers at the dawn of the aviation age. The Montgolfier brothers’ determination, dreaming, and discoveries laid the groundwork for humanity’s ascent to the skies.

Joseph-Michel Montgolfier was born in 1740 in Annonay, France, and his brother and co-experimenter Jacques-Étienne was born 5 years later. Joseph and Étienne came from a large family of 16 children. Their father, Pierre Montgolfier, was a successful paper manufacturer in Vidalon in southern France.