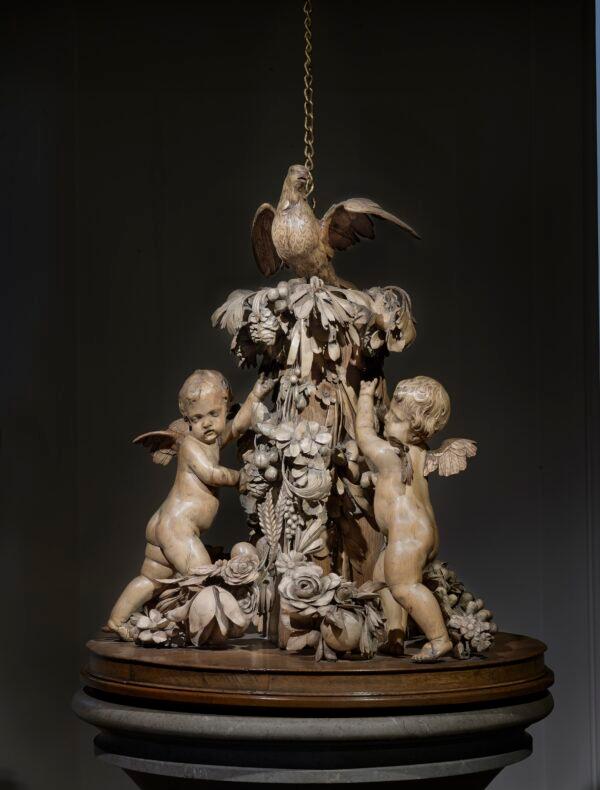

“Stupendous and beyond all description … the incomparable carving of our Gibbons, who is without controversy the greatest master both for innovation and rareness of work that the world ever had in any age,” wrote 17th-century diarist John Evelyn about Grinling Gibbons, the greatest decorative carver in British history.

Baptismal font cover by Grinling Gibbons. All Hallows by the Tower Church, London. All Hallows by the Tower