For the 102 English people aboard the Mayflower, last week four centuries ago was a week they would never forget.

The Mayflower Compact: As an Idea, America Began in 1620, Not 1776

The Mayflower Compact is a quintessentially American story, and the philosophical wellspring from which the United States sprung

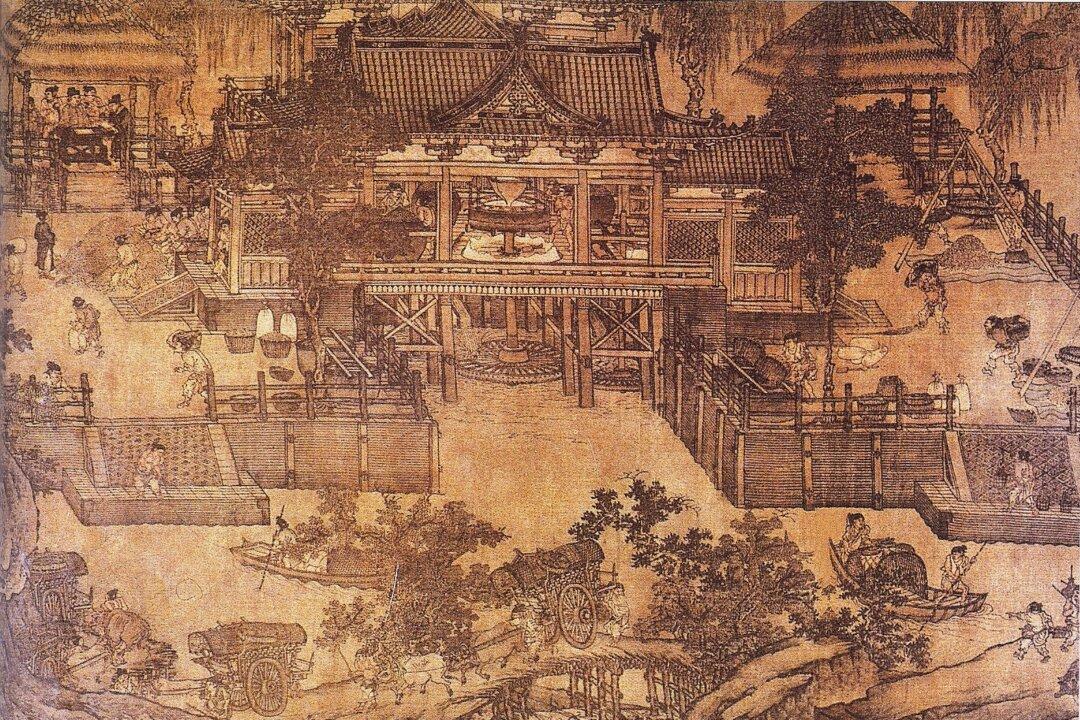

"The Mayflower Compact" by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris, 1620. Public domain

|Updated: