“Public sentiment is everything.”

Deep within the dark and dusty shelves of the Library of Congress lie two of the rarest photographs in American history. The first, bent and burnt with crisp edges crinkling on the sides, is a panoramic image of a crowd milling about on a grassy field and under a gray clouded sky. The second, similar in content to the first, is unique in that a tall stone gateway can be seen in the far distance at the left, while a perfectly erected canvas tent sits just at the right edge of the frame.

For all the scratches and distortions, each image conveys a sense of weighty anticipation. Civilians in stovetop hats and split coats are frozen mid-stride, their faces pointed resolutely toward some unknown destination. Intermixed in the crowd, Union soldiers in full uniform stand casually with their arms resting on their rifles, each poised and ready to be called to attention at a moment’s notice.

Perhaps the most prominent feature of each photograph is the fact that almost every face in both images is utterly indistinguishable—thousands of individual features all blurred and condemned to obscurity by a technology unable to capture movement.

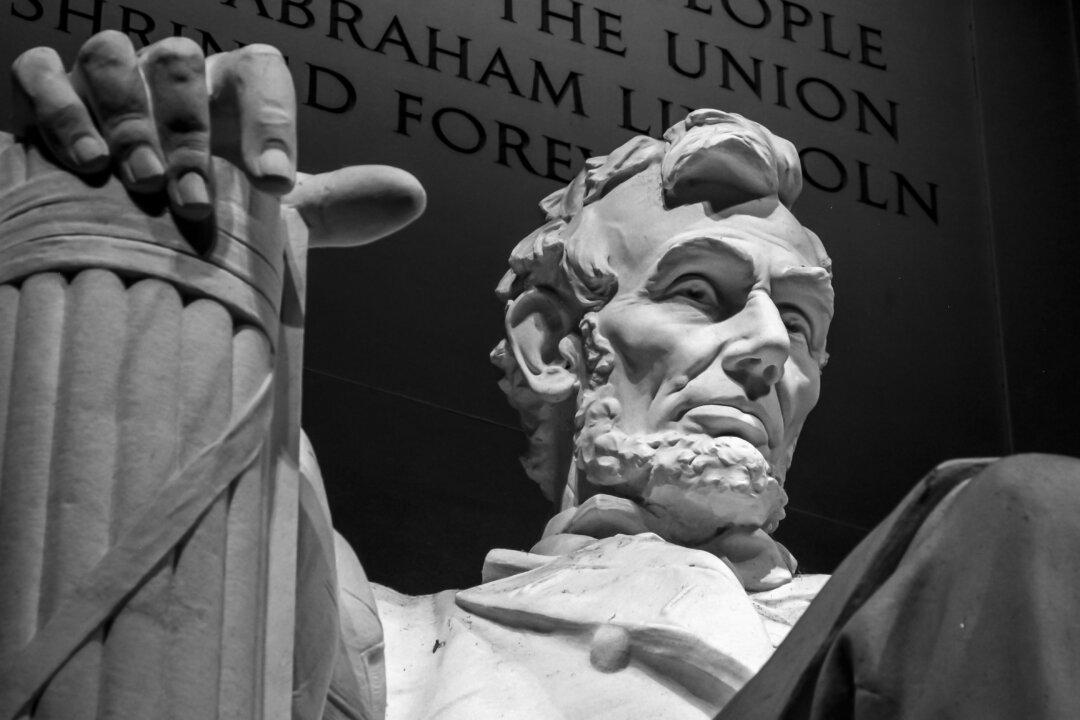

Yet this small historical defect is oddly appropriate, for these photographs were taken on November 19, 1863 at the dedication of the Union cemetery just outside of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania—the day President Abraham Lincoln delivered what is arguably the greatest speech in American history. This day was not meant to be preserved in images or photographs.

Instead, it was a day forever enshrined in the American consciousness by words and words alone.

Almost as revered in history as the actual three-day battle itself, the Gettysburg Address is one of the most well-known pieces of writing in the American lexicon. On the day Lincoln actually gave his short speech, reviews were varied. Some called the speech “dull and commonplace” while others described hearing “a perfect gem.” Whether witnesses appreciated or dismissed Lincoln’s words, it is impossible to dismiss the weight of this singular piece of writing.

But why is the Gettysburg Address taught to generations of Americans almost one hundred and fifty years after it was delivered? What is it about those 278 simple words that allows them to echo in the American consciousness even today?

In part, the answer is because the Gettysburg Address is the essence of communication—the ability to create a message, an idea in other human beings, which lasts beyond lifetimes.

Lincoln’s unparalleled ability to communicate, even from beyond the grave, can be traced to a combination of oratory skills, perceptiveness, and natural talent. As a lawyer, Lincoln learned to respect the power of persuasion—his living dependent on his ability to convince judges and peers that his opinion was correct. His experiences on the bench and on the campaign trail allowed him to hone verbal manipulation as well as master a few tricks of the trade. Perhaps most importantly, Lincoln appreciated the gravity of words, the weight of responsibility to live and act, not just preach. Edward Everett, the famed orator and keynote speaker at the Gettysburg dedication, captured Lincoln’s communication skills best when he penned a note to the then-president the day after the ceremony, “I should be glad if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion in two hours as you did in two minutes.”

The Power of the Public

In times like the present, men should utter nothing for which they would not willingly be responsible through time and in eternity.

—Message to Congress; December 1, 1862

Our government rests in public opinion. Whoever can change public opinion, can change the government, practically just so much. Public opinion, on any subject, always has a “central idea,” from which all its minor thoughts radiate.

—Speech at the Republican banquet in Chicago; December 10, 1856

In this and like communities, public sentiment is everything. With public sentiment, nothing can fail; without it nothing can succeed. Consequently he who moulds public sentiment, goes deeper than he who enacts statutes or pronounces decisions.

—Reply to Stephen Douglas; August 21, 1858

You can fool all the people some of the time, and some of the people all the time, but you can not fool all the people all of the time.

—Fragment; written circa May 1856

No party can command respect which sustains this year, what it opposed last.

—Letter to Judge Samuel Galloway; July 28, 1859

The ballot is stronger than the bullet.

—Fragment; written circa May 1856