Numbers are fascinating: magical numbers, lucky numbers, irrational numbers, imaginary numbers, and so the list of types of numbers goes on. The thing about numbers is that their patterns reveal amazing correspondences to us. So, what’s so special about the number seven?

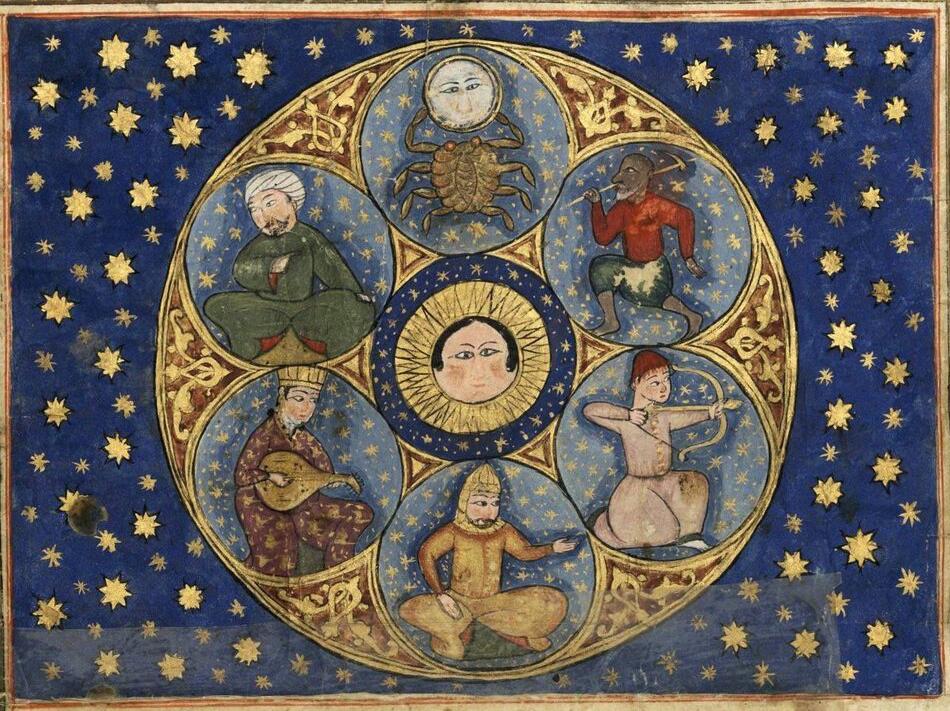

As a general observation, the number seven recurs in many phenomena. The ancients understood that there were seven (visible) planets in the sky: Sun, Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. Modern science disagrees, but ancient astronomy was based on these observations. We count seven continents, we talk of the seven seas, and of the seven wonders of the ancient world.