This coming-of-age classic is about a pride of lions in the African wild. Cub Simba matures to thwart the evil designs of his uncle Scar and succeeds his slain father, Mufasa, as the Lion King. Like all great stories about animals, this is also about humans. It celebrates their finest values and critiques their worst. Plot summary, cast, reviews, and ratings are available at IMDb.com.

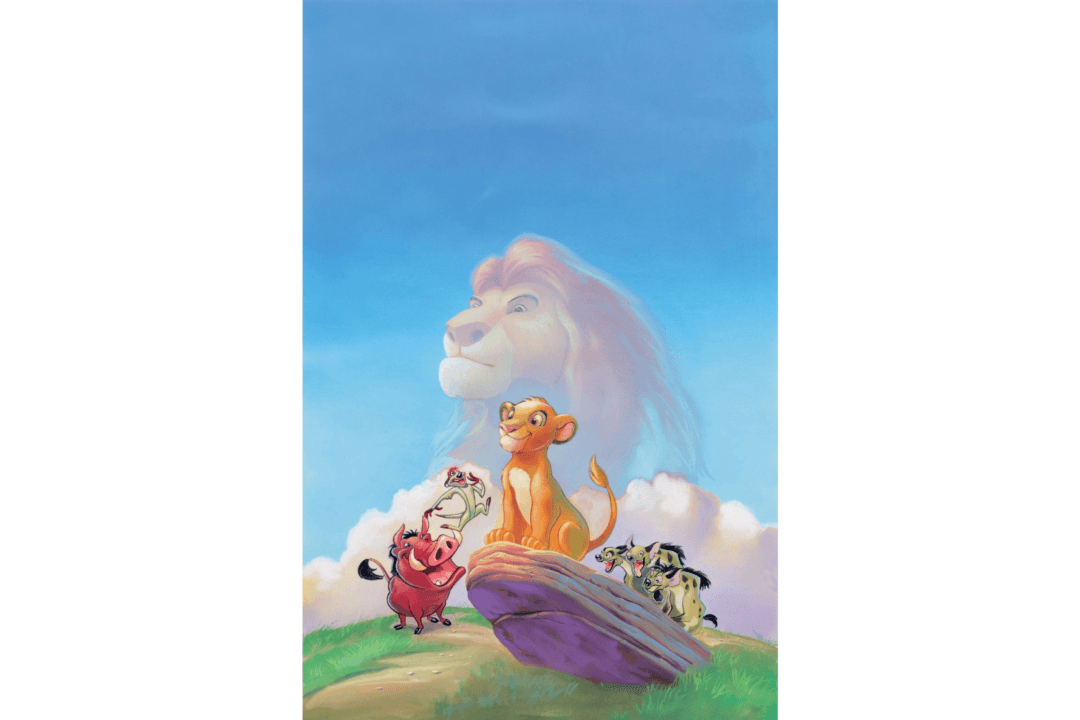

Mufasa guides his cub Simba, in "The Lion King." Walt Disney Feature Animation