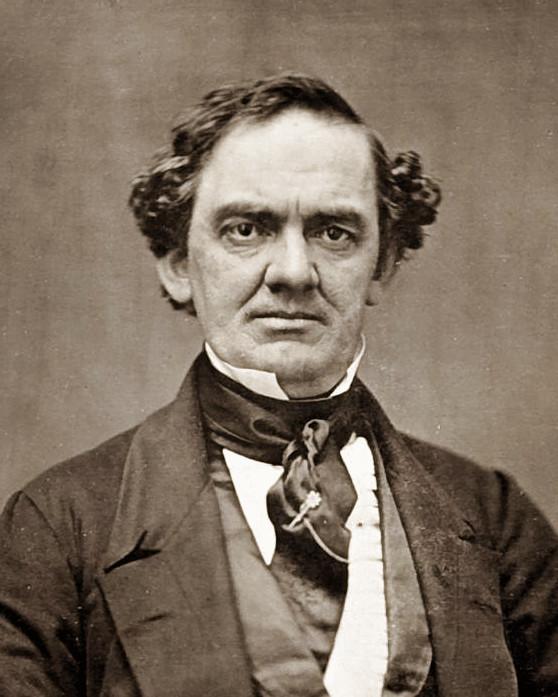

The day after America’s 34th birthday, Phineas Taylor (P.T.) Barnum was born in the small town of Bethel, Connecticut. His upbringing was humble, but he would later become known as the “Great American Showman.” When he turned 12, he traveled to Brooklyn, New York, but by no means in the usual fashion. He was hired to help drive a herd of cattle to the large city. He was enamored with the city that seemed to overshadow his own in both size and scale. In the coming years, New York City would become his home and from there his name would become known throughout the world.

Phineas Taylor "P.T." Barnum, 1851. Public Domain