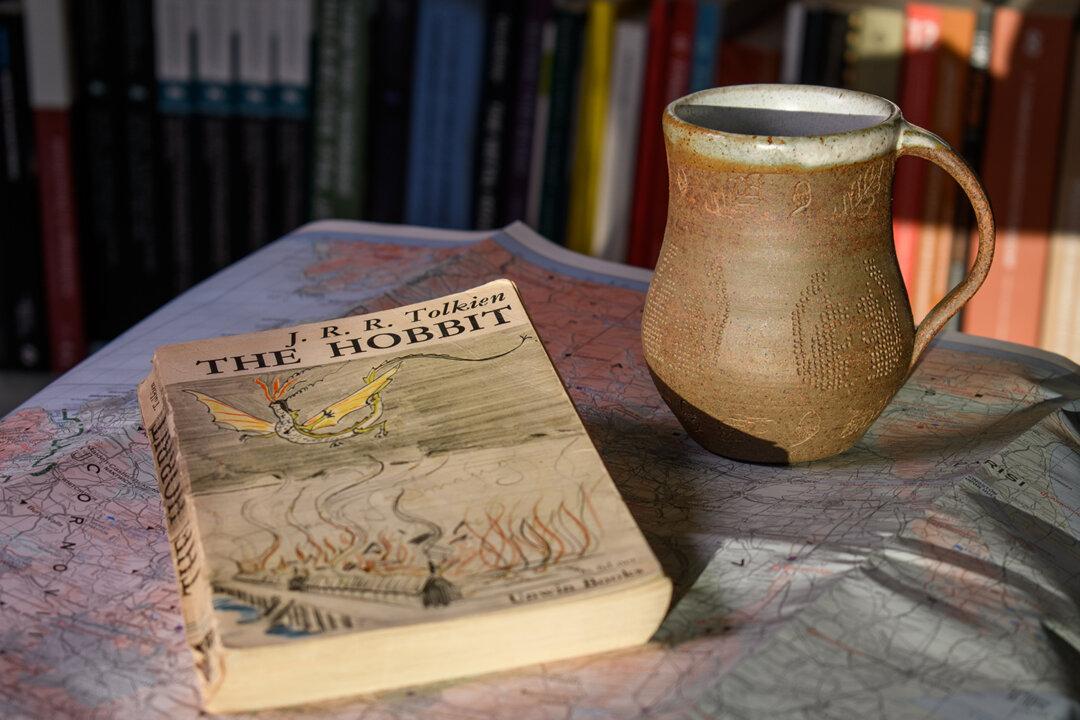

The creation of “The Hobbit” by J.R.R. Tolkien marked the beginning of a modern mythology.

As Randel Helms states in “Tolkien’s World,” Tolkien had once expressed to a friend that he was dismayed the English people had so few myths of their own that they had to borrow from other traditions, and so he had decided to make one himself. Tolkien’s desire to create a new folklore similar to traditional world mythologies was central to his creation of Middle-earth.