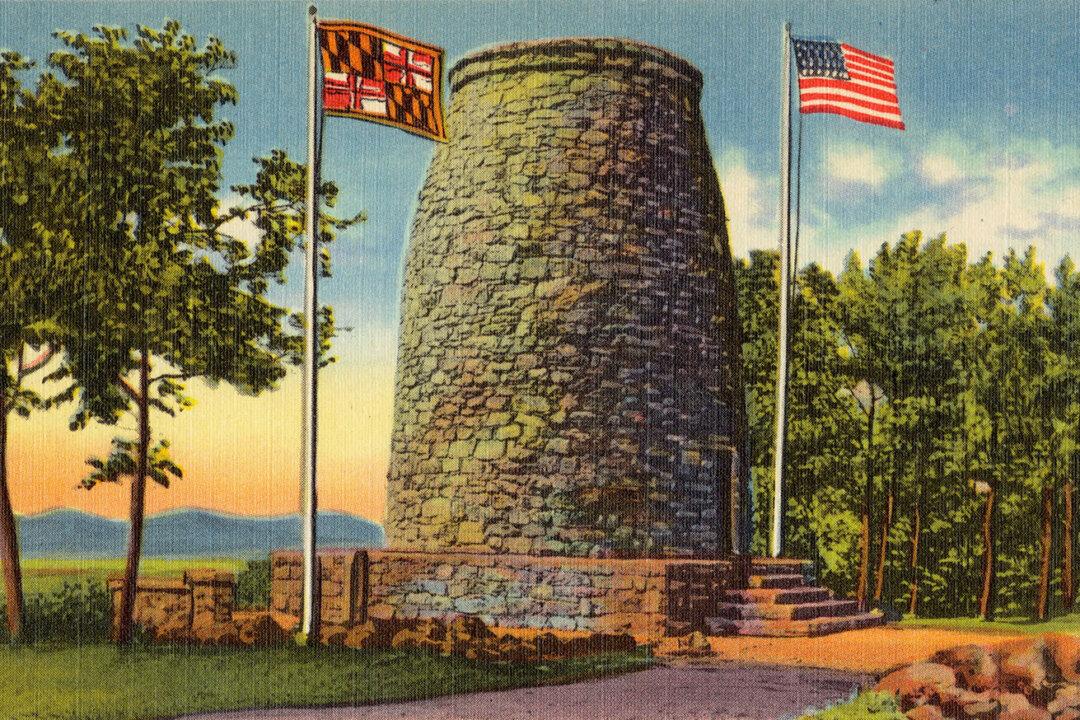

On the morning of July 4, 1827, the citizens of Boonsboro, Maryland gathered in the public square. Almost 500 strong, they marched behind the flag and a fife and drum corps for two miles up a nearby ridge. There, they picked up stones and began to stack them in a circle. In one day, the citizens laid a dry-stone monument to honor George Washington. It stood 15 feet tall on a 54-foot diameter base.

A resident who was there that day wrote, “At the conclusion of our labors, about 4 o’clock, the Declaration of Independence was read from one of the steps of the monument, preceded by some prefatory observations, after which several salutes of infantry were fired, when we all returned to town in good order.” There was, after all, farm work to be done.