Even if most of us celebrate Memorial Day with cookouts and beach parties, the day honoring our fallen soldiers has a history worth knowing.

Today it’s a national holiday, but it wasn’t always a day that united Americans.

It came out of the ashes of a painful Civil War when the wounds of a divided nation were still raw.

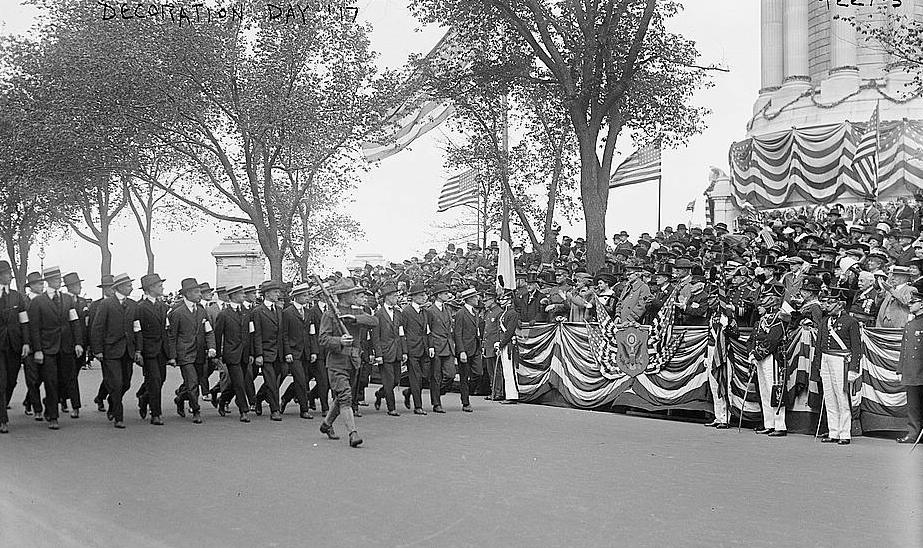

In 1868, three years after the war’s end, Maj. Gen. John A. Logan, declared May 30 “Decoration Day”—a day to honor the war dead by decorating their graves with flowers.

Logan was head of the Grand Army of the Republic, an organization of Union veterans. He declared the day to be “for the purpose of strewing with flowers or otherwise decorating the graves of comrades who died in defense of their country during the late rebellion, and whose bodies now lie in almost every city, village, and hamlet churchyard in the land.”

Library of Congress