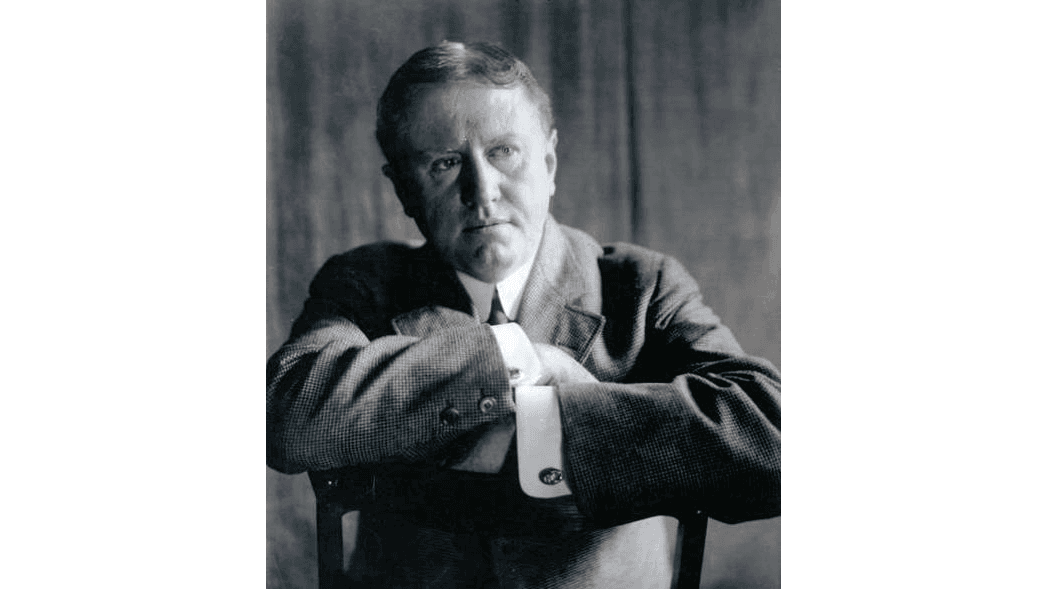

O. Henry is remembered by millions as America’s unparalleled maven of the short story. His stories were pithy, comprehensible, and moving, and there were hundreds of them. A brilliant force of nature, he could produce a pearl of a story in a single night and hardly ever corrected his work from the initial handwritten manuscript. If there ever was someone who seemed to possess an innate talent for putting into words the dreams, desires, and motivations of ordinary people, it was him.

But behind the pseudonym, there was a real man who once received reconciliation and a second chance and never looked back. He’s a sterling example of one who corrected and reinvented himself, who, when at a point in life of utmost crisis, took up their mat and walked.