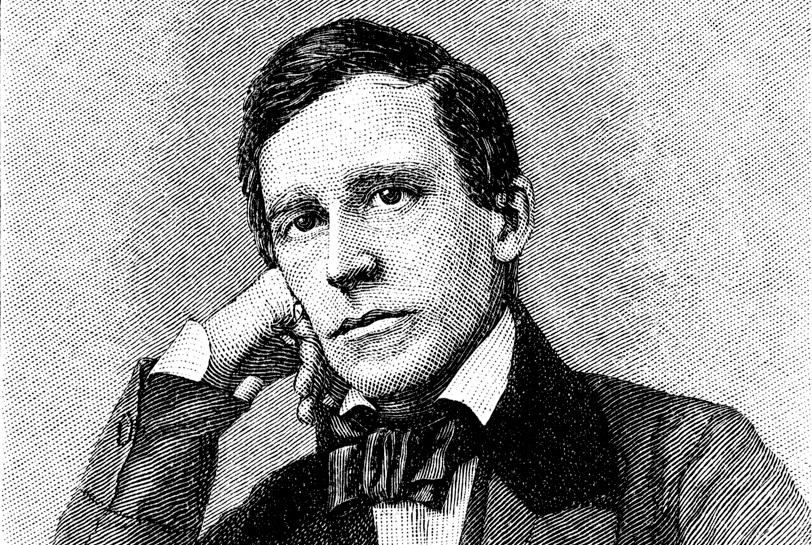

Composer George M. Cohan bragged in a song that he was “born on the Fourth of July,” though in truth he missed that date by 24 hours. His most illustrious predecessor, however, was indeed born on that date in 1826. Stephen Foster, the USA’s first popular songwriter, and by most standards the first professional popular songwriter the world has known, was as American as his birthday.

Noncancelable?

So it is surprising that, except for the removal of a Stephen Foster statue in his hometown of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, little has been done to “cancel” him. And how would one go about canceling songs woven into the very fabric of American life—songs such as “Oh! Susanna,” “Camptown Races,” and “My Old Kentucky Home”?To cancel Foster, one would have to scour the films and recordings of the last century and do some serious scrubbing. “Beautiful Dreamer” alone has been recorded by singers as disparate as Bing Crosby and Jerry Lee Lewis, and its luxuriant strains show up in the films “Gone With the Wind,” “Picnic,” “Shane,” “Duel in the Sun” and, unlikely as it seems, the 1989 “Batman.”