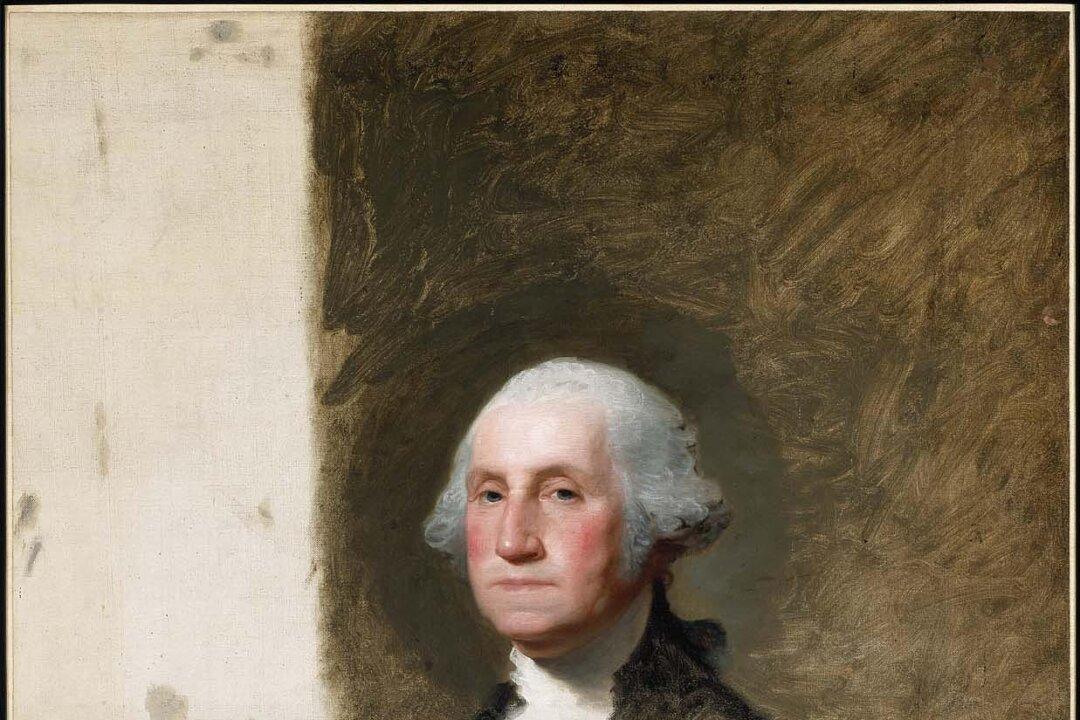

If you’re ever asked to picture George Washington, the first image that comes to mind will most certainly be based on Gilbert Stuart’s portrait of the first president. You know the one, where a distinguished Washington, with flushed cheeks, wears a black velvet suit. His powdered hair has been curled and tied with a black ribbon into a “queue,” a ponytail hairstyle that in Western countries has the hair gathered low in a tail, wrapped around with leather, and tied with a ribbon.

Just take a look at a dollar bill and you'll see Stuart’s Washington on the front, albeit in a mirrored image of the portrait.