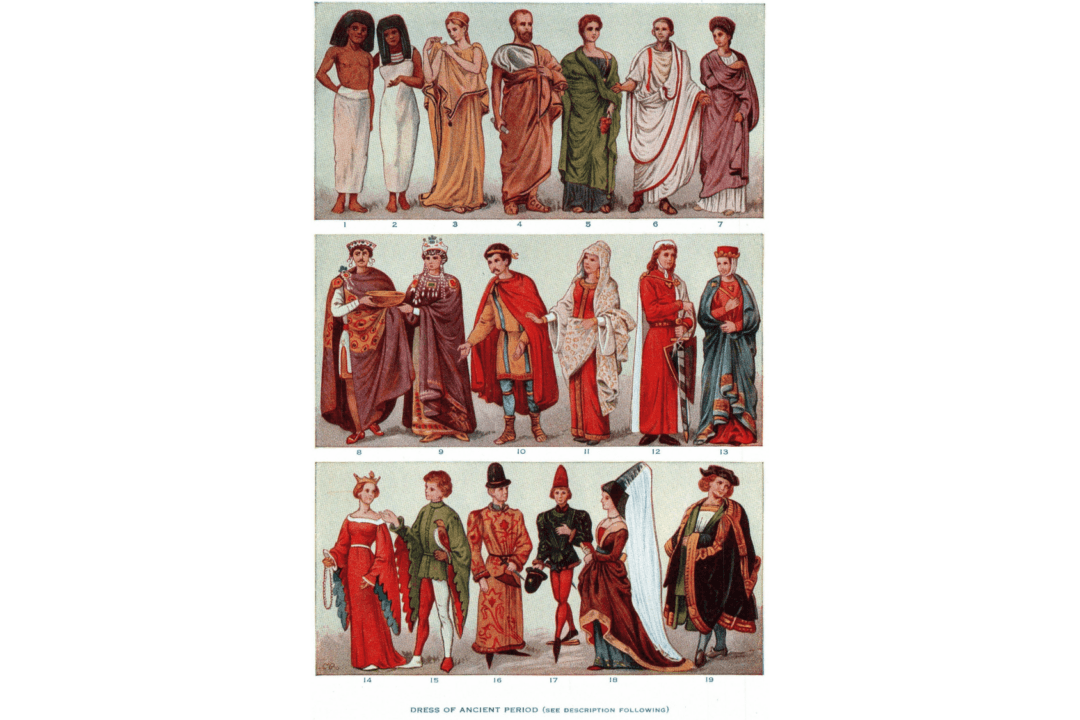

Clothes make the man. Or if you prefer, “vestis feminam facit”: Clothes make the woman.

Throughout recorded history, attire and its accoutrements have signaled to others one’s wealth, power, and station in life; added allure and glamour to the wearer; and reflected the culture of a particular time and place.