AUCKLAND, New Zealand—For nearly 4o years, children’s book illustrator and oral storyteller Lyn Kriegler has worked with some of New Zealand’s most celebrated children’s authors, illustrating 155 children’s books to date. As a keen writer, Kriegler has also been published in books and magazines.

Born in upstate New York, Kriegler comes from a creative family. Her mother is a gifted embroiderer and seamstress, and her father is a retired watchmaker, a jewelry designer, a diamond inlayer, and a highly skilled engraver of precious metals. He was gifted at drawing, but it was always on pewter, gold, or silver, she said.

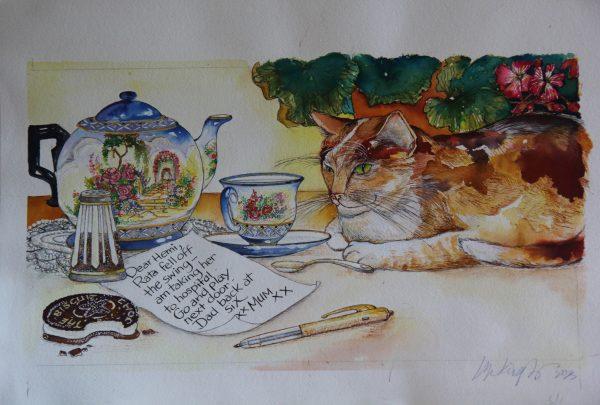

An English teapot, cup, and saucer that Kriegler inherited from her mother are featured in this illustration for Joan de Hamel’s “Hemi & the Shortie Pyjamas.” Lorraine Ferrier/The Epoch Times